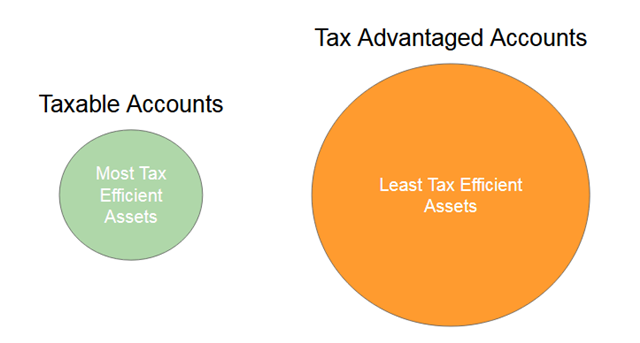

Tax efficient asset placement, also known as asset location (as opposed to asset allocation), is the practice of figuring out which investments should be held in which account based on each investment’s tax efficiency. The idea is that when you have both tax advantaged accounts (such as a 401k, a traditional IRA, or a Roth IRA) and regular taxable accounts, you protect the less tax efficient assets in the tax advantaged accounts and you put the more tax efficient assets in the regular taxable accounts. You pay less tax this way and you get to keep more of your returns.

In Tax Efficiency: Relative or Absolute? we learned that when we measure tax efficiency we can’t look at only the tax rate applicable to an asset. We have to consider both the asset’s expected return and the tax rate. When we look at both angles, it’s not so obvious which of these two asset classes is more tax efficient:

- stocks with a higher expected return but a lower tax rate; or

- bonds with a lower expected return but a higher tax rate

When bond yields were low, a case could be made that bonds were actually more tax efficient than stocks. The tax cost of bonds yielding 2% taxed at 40% is 0.8%. The tax cost of stocks with a 7% expected return taxed at 15% is 1.05%. As a result bonds should be held in taxable accounts. This is against the conventional wisdom that stocks are more tax efficient simply because qualified dividends and long-term capital gains are taxed at a lower rate.

Now that bond yields are a little bit higher, one could argue that the case for bonds being more tax efficient is weaker or it may have reversed. The tax cost of bonds yielding 3% taxed at 40% is 1.2%. The tax cost of stocks with a 7% expected return taxed at average 15% is 1.05%. Stocks are more tax efficient by 0.15 percentage points in this scenario.

I’m not trying to solve which way is correct at this moment. It’s going to depend on the expected returns and the tax rates faced by each individual. Suppose you did the math, and based on your best estimate of the expected returns and your tax rates, you already figured out which way you should go, there’s another limit on your tax efficient placement of assets: the relative sizes of your accounts.

We all know we should max out contributions to our tax advantaged accounts first before we invest in taxable accounts. As a result many people have much more money in tax advantaged accounts than in taxable accounts. When you have 90% of your money in tax advantaged accounts, 90% of your portfolio is protected anyway no matter what assets you hold there. If you didn’t place your assets most tax efficiently, you still only have maximum 10% of your portfolio in a sub-optimal state. The difference between optimal and sub-optimal is very small.

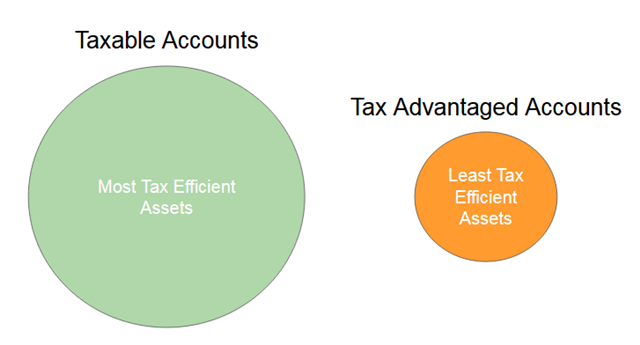

On the other hand, some people have much more money in taxable accounts than in tax advantaged accounts. If you are an entrepreneur who sold a successful business, or if you have very high income, 90% of your money could be in taxable accounts. At most you can only protect 10% of your assets in tax advantaged accounts. The rest 90% is exposed to taxes anyway. If you didn’t optimize the 10%, we are still talking about maximum 10% of your portfolio possibly being in a sub-optimal state. Again the difference between optimal and sub-optimal is very small.

Let’s look at some examples.

Example 1: Small Taxable Accounts

Suppose you figured out stocks are more tax efficient for you than bonds (the conventional wisdom). Your asset allocation for your $100k holdings is 80% stocks 20% bonds.

When you do it most tax efficiently, you would put all your bonds (least tax efficient to you) in the tax advantaged accounts. Your taxable accounts would have 100% in stocks. It would look like this:

| Taxable Accounts (10%) | Tax Advantaged Accounts (90%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Optimal Placement | $10k in stocks $0 in bonds |

$70k in stocks $20k in bonds |

When you ignore tax efficient placement and you just naively hold the same allocation across all your accounts, both your taxable accounts and your tax advantaged accounts will have the same 80% in stocks 20% in bonds. It would look like this:

| Taxable Accounts (10%) | Tax Advantaged Accounts (90%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Naive Placement | $8k in stocks $2k in bonds |

$72k in stocks $18k in bonds |

What’s the difference between the two? We are talking about where 2% of your portfolio should go. Where you put 2% of your portfolio just doesn’t make much difference. If having $2,000 more in bonds versus stocks in your taxable accounts will cause you to pay 0.15% more in taxes on the $2,000, we are talking about $3/year. It’s just not worth worrying about.

Example 2: Small Tax Advantaged Accounts

Now suppose you just sold your successful business. As a result you have 90% of your assets in taxable accounts. Because you have won the game, you decided to go with a more conservative asset allocation for your $2 million portfolio: 50% in stocks 50% in bonds. You also decided to go with the conventional wisdom and treat stocks as more tax efficient.

When you do it most tax efficiently, you would make your tax advantaged accounts hold 100% bonds (least tax efficient to you). Your taxable accounts would hold the rest. It would look like this:

| Taxable Accounts (90%) | Tax Advantaged Accounts (10%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Optimal Placement | $1 million in stocks $800k in muni bonds |

$0 in stocks $200k in bonds |

When you ignore tax efficient placement and you just naively hold the same allocation across all your accounts, both your taxable accounts and your tax advantaged accounts will have the same 50% in stocks 50% in bonds. It would look like this:

| Taxable Accounts (90%) | Tax Advantaged Accounts (10%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Naive Placement | $900k in stocks $900k in muni bonds |

$100k in stocks $100k in bonds |

Either way your taxable accounts will hold at least $900k in stocks and $800k in muni bonds. The difference between the most optimal placement and the naive across-the-board placement is only about where $100k out of $2 million should go. That’s only 5% of your portfolio. It just doesn’t make much difference. Again if holding additional 5% of your portfolio in muni bonds versus stocks in your taxable accounts will cause you to lose 0.15% more to taxes on the 5%, we are talking about a difference of 5% * 0.15% = 0.0075%. It’s just not worth worrying about.

***

Sometimes we hear people say target date funds are not good for taxable accounts because target date funds have taxable bonds in them. Putting aside whether bonds are actually more tax efficient than stocks due to their lower expected returns, when most people have much less money in taxable accounts to begin with, it just doesn’t make much difference in real life whether you try to do it most tax efficiently or you just have the same asset allocation across all your accounts.

Don’t be afraid to invest in a target date fund in a taxable account when your taxable account is relatively small to your tax advantaged accounts. Having the same target date fund or the same asset allocation in all your accounts makes it so much easier when you contribute different amounts to different accounts at different times.

When you hear some “advanced” strategies, such as rebalancing, tax loss harvesting, or in this case tax efficient asset placement, you should assess how much the strategy really applies to you and how much difference it actually makes. Tax efficient asset placement is directionally correct but the relative sizes of your accounts can put a serious limit on its effectiveness. It may be worth doing when your accounts are relatively equal in size but it can be safely ignored when that’s not the case.

I did the two examples with a 10/90 split and a 90/10 split between taxable and tax advantaged accounts. For other splits and asset allocation, you can use the spreadsheet embedded below to compare the optimal placement and the naive placement and see how much difference it really makes to you. Please only change the numbers in blue to your own assumptions. The rest of the spreadsheet will calculate automatically.

Sometimes it’s OK to be naive.

Learn the Nuts and Bolts

I put everything I use to manage my money in a book. My Financial Toolbox guides you to a clear course of action.

TheGipper says

Another kicker is the (unexpectedly) high percent of dividends that are non-qualified even for supposedly efficient funds like Vanguard Total Stock (VTSAX) and Vanguard Total International (VTIAX). I know I was surprised when I looked at my 1099 from Vanguard this year. This also occasionally reverses the conventional wisdom of holding international funds in a taxable account for the foreign tax credit. Even with this, many years VTSAX is more tax efficient than VTIAX.

In the end, it doesn’t matter much. Since a taxable account is often used for intermediate term goals (cars, college, weddings), I like bonds (municipal) in a taxable account even more so, to lessen the cap gains hit.

Moira says

If you are under 70 1/2 and your annual budget includes significant charitable giving, then holding stocks in taxable is far more tax efficient than holding bonds in taxable. This is true even if you don’t itemize deductions because you can donate your most highly appreciated securities without recognizing the capital gain income as part of your AGI.

Once you are over 70 1/2, then the possibility of QCDs arises and this muddies the comparison somewhat.

Holding stocks in taxable can also be very tax efficient if you are planning to make significant gifts (e.g., wedding, graduation presents) to loved ones who are in lower tax brackets than you are. Also very tax efficient if you are planning bequests.

Charitable giving is a large component of my annual spending so this is a significant consideration for me.

Harry Sit says

This post is not about whether holding stocks in taxable is more tax efficient than holding bonds. It’s about how much difference the optimal placement makes over holding the same allocation in all accounts. We need to quantify the magnitude and not just look at the direction.

If you think a significant portion of your stocks in taxable will go to bequests or charities, just lower the average tax rate on stocks in the spreadsheet. Make it all the way to 0% in an extreme case for someone whose income is low enough to pay 0% on qualified dividends and long-term capital gains forever, and no state income tax. The tax savings from the optimal placement will be higher in that case. How much higher is the question. The spreadsheet helps quantify that.

Physician on FIRE says

There are certain things at the margins that I do suboptimally (spending from a 529, for example) because it makes little difference in the grand scheme of things. I’ve never considered asset location and tax-efficiency to be one of those marginal things, though.

It’s important to recognize that taxation in a taxable account can be highly variable, particularly when it comes to qualified dividends and capital gains, which can be anywhere from 0% (taxable income under ~78,000 MFJ) to over 37% (20% + 3.8% NIIT + 13.3% CA state income tax).

[non-muni] Bond yield in taxable, on the other hand, will be taxed at your marginal tax rate.

Good discussion overall and food for thought, but I’m glad my portfolio is structured in a way that minimizes my tax burden — I’m holding about half my retirement portfolio in taxable.

Best,

-PoF

Sven says

Reinforcing what PoF wrote, one needs to be very careful on the tax rate for long term capital gains and qualified dividends. During accumulation and holding broad index funds in taxable, there should be little or no capital gain distributed or realized, so no gains tax drag. Mostly qualified dividends would see 0, 15, 20, or 23.8% (plus state) tax.

Now in retirement, I am living off my taxable account. I find that I tax-gain harvest one year up to the top of the 0% bracket to raise funds, then spend the next two years using the cheap bracket space to do Roth conversions. I am still paying 0 in LTCG taxes. I pay the qualified dividend tax two years out of three. With 2% dividend yield and 5% capital appreciation, my tax rate for equity should be 5%/7% x 0% + 2%/7% x 15% x 2/3 = 2.9%/year, on average.

Harry Sit says

The good thing is the spreadsheet can accommodate any tax rate. If you think your average rate is 2.9%, put in 2.9%. If someone else is facing 37%, put in 37%. Because it’s a spreadsheet, we can also try different numbers and see how the results change. What if you move to a state with income tax and the 2.9% changes to 5%? What if laws change down the road and the average rate becomes 10%? Try 10 different scenarios then you will know when the optimal placement is more effective and when it doesn’t make much difference.

Doctors On Debt says

I enjoyed this article.

I realize its focus is on the taxes, but don’t forget to consider fees as well when determining asset location.

I am in what I consider a “bad” 401(k). I have chosen to place all of my bond holdings in it because, although I think for tax purposes my bonds would be better in a taxable account, I expect them to grow slower over time.

Because of that expected slower growth, I am hoping to minimize the fees I will pay in my high-fee 401(k).

-DoD

Ritch says

An excellent post that provides good food for thought. Thanks for the Spreadsheet tool.

While I agree with PoF that for some in higher tax brackets (especially those in high tax states) asset location is certainly worth calculating and optimizing, I believe for many people it’s not a significant issue. Also, tax laws can and do change, so the steps we take now are subject to the future whims, wishes and wants of our elected policy makers. And as you said, some conditions (like interest rates) also fluctuate (sometimes greatly) over time, which increases the likelihood that our projections will not be as precise as we might like. Obviously none of that should keep us from doing what we think is prudent today, but it can impact the ultimate outcome in a way that differs from what we originally anticipated.

IMO, Financial Advisors sometimes oversell the monetary benefit of optimizing Asset Location in an effort to justify their 1.00% (or higher) AUM fees. For many Mass Affluent folks (and some with even greater investment portfolios) whose income amounts and tax rates are moderate, I think the financial value gained by such optimization isn’t as substantial as it’s made out to be.

Harry Sit says

No doubt advisors have an incentive to show sophistication. When they assume clients will pay the fee anyway, it becomes their fiduciary duty to give clients “the best.” Clients should understand whether they are better off paying more taxes than paying the advisor.

I also see some DIY investors jump in with both feet because the optimal placement by definition is “the best.” They think it’s a must-have, not realizing how much difference it really makes to them and whether other things are of much higher priority than optimizing asset placement.

Rick R. says

I’ve been looking at short to intermediate term actively managed bond ETF’s (primarily from Pimco) as a place to stash cash, given my fear of interest rate risk. My understanding is that ETF’s for any asset class, whether they’re paying a fixed income yield on corporate bonds or a stock dividend, are more tax efficient because of rules about ETF’s and their tax structure (none of which I really understand). Shouldn’t consideration of such instruments come into play when considering placing bonds in taxable accounts?

Harry Sit says

It’s not true. ETFs don’t have any advantage in dealing with fixed income interest or stock dividends. They must distribute them and make the investors pay taxes on the interest and dividends in the same way as open-end mutual funds. ETFs only have an advantage in _internally realized_ capital gains. Through a mechanism unique to ETFs, they can minimize the internally realized capital gains, and therefore postpone the capital gains until you sell. If you must sell ETFs for your own spending (versus leaving to heirs or donating to charities), you will realize those gains eventually and pay taxes at whatever tax rates that apply at that time. Broad-market index funds don’t generate much internally realized capital gains anyway. So even when ETFs have an advantage, the advantage is very small.

Rick R. says

Thanks for the clarification. I was confusing capital gains with dollars earned via interest and dividends. I did know that selling ETF shares in a taxable account, assuming they had appreciated in value, would require tax payments on cap gains. Thanks again.

Brian says

1. Let’s not forget the 3.8% tax on amounts more than 250k…supposedly just on investments but it seems to be when AGI gets above 250k….little written about this nasty surprise ( eg which includes Roth conversions)

2. The tax credit on international funds seems to be overrated…the Vanguard Total Intl Stock fund seems be less than the expense ratio…ie in the 0.1-0.2% range. Trivial but not seen anyone write about it yet this asset usually advocated for taxable accounts for this trivial reason

Robert Bradley says

More robust models, such as those you can model at http://www.nestegged.com , show a potential benefit of hundreds of thousands of dollars (tax and risk adjusted), when you factor in both your lifetime income from the portfolio, and your heirs’ taxes.

Sample screenshot: https://imgur.com/a/uYm3yhH – granted you only make an extra $300k on $4M in total value here (draw down plus heirs), but correct asset location is still important.

Denis says

Nice spreadsheet tool.

However, I take an issue with this statement.

“The tax cost of stocks with a 7% expected return taxed at 15% is 1.05%.” That would only be correct if you sell your whole stock portfolio after 1 year, pay the capital gain tax, and reinvest the after-tax amount.

In reality, if you buy and hold for years, you pay 15% on the dividends of about 2% from a broad stock market index fund for the tax cost of 0.3%.

The eventual sale will result in a capital gain tax of 15% on the remaining 5% of annual return. This tax will effectively be applicable to a multi-year period of holding these stocks. For a hold period of 15 years, the capital gain tax cost can be approximately estimated at 5%*15% / 15 years = 0.05% per year.

The total tax cost of holding the stocks for 15 years is then 0.3%+0.05% = 0.35% which will almost always be smaller than the tax cost of non-muni bonds.

For almost all buy-and-hold buyers, stocks are more tax efficient.

Harry Sit says

The 15% was just an example for the average tax rate over the entire holding period after taking into account all taxes, including federal, state, 3.8% surtax, 5% extra tax for high income earners, effect on Social Security benefits, etc. It wasn’t meant to match the federal tax rate only on capital gains. If you think your average rate over your holding period is only 6%, use 6%.

We are not debating which is more tax efficient here. We are looking at how much difference the extra tax efficiency makes if you take full advantage of it versus just doing a naive across-the-board allocation when your account sizes are lopsided one way or another.

Denis says

Harry, the problem is that most people can easily miscalculate tax rates applicable to bonds and stock holdings in a taxable account. Without good guidance on correct inputs, the tool will not give the correct estimate.

If you only wanted to make a point that the benefit of tax-efficient asset placement is small then I agree. A good way to do it is to take the extreme case of 50% in stocks, $500k in taxable / 500k in tax-advantaged, and 0% tax rate on stocks (for the lowest tax brackets). The difference between naive and optimal placement in this case is 0.26%. For all other cases, it will be smaller, usually, much smaller.

TJ says

My fear of going with the convenience of target date in taxable, is that at the end of accumulation phase, I could have a substantial taxable account with a lot of embedded gains. Maybe the convenience is worth the potentially higher tax cost. (E.G. no foreign tax credit, Taxable bonds instead of Muni’s)

I’m guilty of tinkering my portfolio over time and maybe it would be better to just set it and forget it with a target date fund, because it’s “good enough”, but doing so would also eliminate the easy ability to take advantage of the retail investor perk to easily “double the bond yield” as you had posted about years ago.

Harry Sit says

If you do the conventional placement and you only keep stock funds in the taxable account, you will have more embedded gains. I’m seeing far fewer “double he bond yield” opportunities this time around. In the end, the relative sizes of taxable versus tax advantaged accounts still matter. If your taxable accounts are relatively large, and your tax rate is sufficiently high, munis versus taxable bonds still makes a difference. To most people, their taxable accounts are relatively small, and their tax rate isn’t that high, investing in a target date fund in their taxable accounts works just fine.