From time to time, people ask why not invest 100% in stocks. This question is always met with astounding objections. People say:

- It’s too risky.

- Very few will be able to handle the heat, i.e. most likely you will sell at the bottom.

- Inexperienced investors who haven’t been through a severe bear market are overconfident of their risk tolerance.

- The thought must be misled by the recent run-up in the stock market.

Someone on the Bogleheads investment forums collected the instances of people asking about 100% in stocks as a contrarian indicator of market tops.

Target Date Funds: 90% in Stocks in the First 15-20 Years

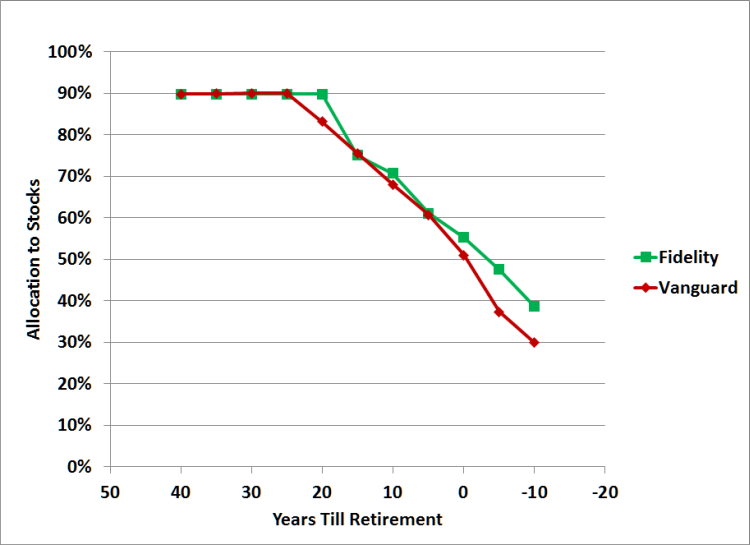

These objections are legit, but I also noticed that Vanguard sets its target date funds at 90% in stocks for 15 years, from age 25 to age 40. Fidelity does it for 20 years, from age 25 to age 45. I had this chart in the article about Fidelity Freedom Index Funds:

90% in stocks is obviously not 100% in stocks. However, is there a big difference between 90% in stocks and 100% in stocks? If 100% in stocks is bad, is 90% in stocks that much better?

Similar Loss From Crash

I looked at the peak-to-trough performance between October 2007 and March 2009. During this period, a portfolio 100% invested in stocks (70:30 mix between US stocks and international) fell 55%. The Vanguard Target Retirement 2050 fund, which had 90% invested in stocks plus 10% in bonds, fell 50%.

Having 10% invested in bonds helped, a little bit. Instead of seeing your portfolio fell 55%, you saw your portfolio fell 50%. Is that much consolation though? If someone would sell in a panic when their portfolio falls 55%, how is it going to stop them when their portfolio falls only 50%?

At 10% in bonds, the portfolio’s performance and volatility are going to be driven largely by the 90% in stocks. There’s no way that a small decoration such as 10% in bonds will make much difference. The decoration is there to plant the seed of the diversification concept early on. Even though it doesn’t do much yet in reality, it will be useful in the future.

Reasons for High Allocation to Stocks

If 100% in stocks is bad, 90% in stocks isn’t much better. Then why does Vanguard put people into 90% in stocks for 15 years? Is Vanguard being irresponsible or reckless? Does Vanguard know something we don’t?

It does. Vanguard has a lot more data than we do. It serves millions of retirement plan participants and millions of investors with IRAs and other accounts. It knows how much people make, how much they contribute, and how they behave during bull and bear markets.

Vanguard shares some of the data with us in its annual How America Saves report. According to the report, even during the chaotic 2008, only 14% of the retirement plan participants initiated any trades, half of which were buying stock funds instead of selling stock funds. The idea that everyone rushes out to sell when the market drops is simply not true, at least not true in retirement plan accounts.

Having 90% in stocks, or 100% in stocks for that matter, is also recognizing the difference between investing a lump sum and investing a stream of contributions over time. It is risky to invest 90% or 100% of a lump sum in stocks with no more new money coming in. Not quite so when you are investing a stream of contributions in the early years, when the vast majority of the contributions are going to be made in the future. Holding back early only means buying at higher prices in the future.

Let’s not kid ourselves in thinking there’s a big difference between investing 90% in stocks and investing 100% in stocks. Those who invest 90% or 100% in stocks aren’t necessarily overconfident inexperienced investors who are destined to sell in a panic at the market bottom. The vast majority actually hold it and add to it like clockwork. Vanguard has data to prove it.

Conclusion

If you are young, investing 100% in stocks isn’t too far from what Vanguard and Fidelity recommend in their target date funds. If you’d like to be a little more aggressive, it’s perfectly OK. Just remember not to sell in a panic when the stock market crashes.

Learn the Nuts and Bolts

I put everything I use to manage my money in a book. My Financial Toolbox guides you to a clear course of action.

LostPension says

One additional reason I would see in having 90% invested in stocks rather than 100% invested in stocks, with the 90% plan you have cash to put to work on dips and irregular October dives in the market.

Harry Sit says

Unfortunately it doesn’t do much on small dips such as the one we saw in late September to early October. The market dropped less than 10%. Suppose you start out with $900 in stocks and $100 in bonds. When stocks drop 10% and bonds stay flat, you have $810 in stocks + $100 in bonds = $910 total. To rebalance back to 90% in stocks, you sell $9 from bonds to buy stocks ($910 * 0.9 = $819). When the market recovers, your $9 purchase at the dip bottom if you timed it perfectly will earn you $1 extra than if you didn’t do anything at all. That’s $1 extra in a $1,000 portfolio: $1,001 versus $1,000, assuming you timed the dip perfectly, less if you rebalanced too soon or too late. Not a big deal at all.

FinancialDave says

To be honest, the difference of 100% equities or 90% equities in retirement could be the difference of running out of money in 31 years or having the money last 40+ years, if you happen to hit the worst 40 years in history. I doubt anyone who did run out of money would think it was a trivial difference.

Feel free to explore an article I wrote on Safe Withdrawal rates:

http://seekingalpha.com/article/2709635-safe-withdrawal-rates-part-1-retirements-4-percent-rule

Dave

Harry Sit says

I agree “in retirement” and “worst 40 years in history” are a completely different game. Here’s talking about the first 15 years in a 40-year accumulation journey.

marketmap says

The plain vanilla belief in the “low cost” fund industry is that “investors can tolerate risk”, especially younger aged investors, and should be able to “ride out” the volatility. We think that exposing retirement savings to risk ( even with a “60/40 balanced portfolio ) without exploring risk mitigation, is lazy, biased thinking. The future of retirement investment management and maximized asset growth trajectories lies in risk management. Chart 18 shows the kind of drawdowns that investors have had to endure : http://stockmarketmap.wordpress.com/2014/03/

FinancialDave says

Marketmap,

It appears that most endured the worst in their accumulation history quite well (2008). Of the 28% that made any change in their 401k at all, about half bought more, while the other half (14% of all 401k participants) did sell some funds. It is not really risk mitigation and more complicated strategies that we need, it is more about getting those (especially Millennials) engaged and investing. In fact there have been articles recently that suggest Millennials have over 50% of their investments in cash:

http://seekingalpha.com/article/2682355-setting-up-a-portfolio-that-millennials-can-relate-to

These people don’t need dividend paying stocks, that are hard to manage, or small cap funds that are more aggressive, they need what has proven to be less aggressive and still has a chance of beating the market index such as the SP500.

fd

Eric says

I’ll just point out, per DFA’s Matrix Book, $1 in the all-equity global stock index grew to $201 from 1973-2013 and $128 in a mix of 80% of those stocks and 20% in short-term bonds. I’d assume a 90/10 grew to $164. I’d think almost $30 more ending wealth over a lifetime might be worthwhile for someone able to accept 5-10% greater drawdown every few years?

Obviously 100% in stocks ain’t for everyone, but I fail to see what benefit 10% in bonds would do for you.

Fabian says

author is missing the point. 90/10 is better because it gives you option to not sell stock when you need money (which is likely at a time when stocks are low)

Harry Sit says

If you need more than 10% of your portfolio’s value, you still have to sell stocks. If you only need 10% of your portfolio’s value, by the time you need it, the money kept in stocks may very well have appreciated enough that you still come out ahead even if you sell. Finally, don’t they say never cash out your retirement account? Find the money you need elsewhere.

JD says

If 100% equities is good early on in a saver’s life, why not 150%? Why not extrapolate that sloped line back up all the way? For that matter, why only 10% bonds? Nobody bats an eyelid if a 25 year old in stable employment heads out and gets himself an 80% mortgage, and the consequence of this particular bet going sour might be homelessness… Compared to wiping out what’s likely at this early age to be a fairly small portfolio of equities, which would be uncomfortable but hardly the end of the world. Surely sensible retirement planning would dictate that equity risk should be diversified effectively over time by using leverage early on?

Harry Sit says

Going 150% or using leverage costs money and subjects the investor to margin calls. You can’t use margin in a retirement account anyway. That’s why.

Erick Brunet says

Thank you for sharing the article. It’s very interesting. Hope to hear more from you.

Timothy B. Lee says

I think this is the answer to your question:

http://www.aaii.com/journal/200601/images/portstrategies_figure1.gif

The slope of that line shows the marginal tradeoff between expected return and expected volatility for any given stock/bond mix. You’d never want a 100 percent bond fund because an 80 percent bond/20 percent stock fund actually has higher returns *and* lower volatility, since stocks and bonds are not strongly correlated.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, going from 90 percent stocks to 100 percent stocks gives you only a small increase in expected return but a large increase in volatility. If you have a long time horizon and a healthy appetite for risk, that might be fine. But for most people adding 10 or 20 percent worth of bonds provides a much-appreciated reduction in volatility with only a modest impact on expected returns.

Harry Sit says

The horizontal distance and the slope between each dot on the right side of the curve (after 60% in stocks) look pretty equal to me. I wouldn’t say “going from 90 percent stocks to 100 percent stocks gives you only a small increase in expected return but a large increase in volatility” as if 90% is a sweep spot or 100% is a bad spot to be avoided. Going from 90% to 100% looks to be the same as going from 60% to 70%, from 70% to 80%, or from 80% to 90%.

Timothy B. Lee says

Sure, I think 80/20 or 70/30 are reasonable options too. The point is that adding bonds to an all-stock (or nearly all-stock) portfolio gets you a lot less volatility with only a small cost in terms of lower returns.

Harry Sit says

I disagree with “a lot less volatility” if we are talking about 10% more in bonds. Of course whether a drawdown of 50% vs 55% is a lot less is in the eye of the beholder. If you really want a lot less volatility you will need a lot more in bonds and you will incur more than a small cost in terms of lower returns. Just tweaking 10% is not going to do it.

Alex says

I haven’t seen any studies on this but I’ve always assumed that the 10% in bonds is there to boost returns in the event of a black-swan drop in the stock market. A 55% vs 50% draw-down isn’t a big deal, but 80% vs 72% means an instant 40% boost on the subsequent bull market starting point, and that’s ignoring the appreciation in long-term treasury bonds during a severe stock drawdown.

FinancialDave says

Alex,

I don’t think you are thinking about this in the correct way — for young investors, and pre-retirement.

In the first place, other than the risk of an investor pulling money out of his investments in a downturn, all that extra bonds will do to a pre-retirement account is DECREASE the return, in the long run. In fact the best thing that can happen to you while you are accumulating funds for retirement is that the market goes down and you add more funds at a better value.

The long term total return of your account is the average of the bond return and the equity return. To make the math easy assume a 50/50 split. If the equity return is 10% and the bond return is 4%, your combined return for the 50/50 split is 7%, while a 100% equity return does 10%. That means that a $10,000 investment made at age 25 will grow to $452,593 by age 65 and in the 50/50 split to only $149,745 under the above returns.

You get no “instant boost” as you suggest by having bonds in your account, as the equity portion in the account has still gone down by 40-50%, even if the total account has only gone down by 30%.