Most people are familiar with the concept of the progressive income tax system in the U.S. As your income goes higher, you pay a higher tax rate on your additional income.

Some people mistakenly think that getting a bonus that pushes them into a higher tax bracket will make them worse off than not getting the bonus. That’s not true because a higher tax rate isn’t imposed on the entire income. It only applies to the portion of the income that crosses the line and lands in the higher tax bracket. That’s why the phrase “tax bracket” in common parlance is really the marginal tax bracket. It applies to the income on the margin.

Marginal Tax Rate >= Tax Bracket

If you paid more attention to taxes, you would also know that your marginal tax rate isn’t necessarily those in the published tax brackets — 10%, 12%, 22%, 24%, 32%, etc. Other parts of the tax laws can give you a high marginal tax rate even when you don’t have a high income.

I showed this effect in Receive EITC, Contribute to Traditional 401k Not Roth 401k. People with a low enough gross income to qualify for the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) face a marginal tax rate as high as 41%. Mike Piper also explained this phenomenon well with more examples in his blog post Marginal Tax Rate: Not (Necessarily) The Same As Your Tax Bracket.

Some authors (not Mike Piper) use incendiary language and call it the tax torpedo, tax time bomb, etc., especially when it relates to taxation on retirement income such as Social Security income.

The Root Cause

An unusually high marginal tax rate at a modest income almost always results from losing some tax benefits as your income goes up. The additional income gets taxed at the normal rate but losing some other tax benefits at the same time compounds the effect.

For instance, if an additional $1,000 of income normally gets taxed at 12% but you also lose $300 in other tax benefits due to this higher income, your taxes will go up by $120 + $300 = $420. That’s a 42% marginal tax rate, not 12%. People caught by this are naturally upset. They say they’re paying a higher tax rate than the rich.

The thing is, when you have an unusually high marginal tax rate, you’re actually paying lower taxes than other people with the same income. In other words, the unusually high marginal tax rate is a blessing, not a curse.

Glass Half Full

You pay lower taxes than other people with the same income because when you’re losing some tax benefits, you have something to lose to begin with. As you lose some of those tax benefits, you still get to keep a part of them.

Income isn’t the only qualification criterion for tax benefits. Keeping some tax benefits makes you pay lower taxes than other people with the same income who aren’t eligible for those tax benefits for other reasons.

It’s a classic story of a glass half full or half empty. Losing some tax benefits gives you an unusually high marginal tax rate, bad! Keeping some tax benefits lowers your taxes, good! Should you lament the loss or savor the part that you keep?

Let’s look at some real-world examples.

Tax Credit Phaseout

The American Opportunity Credit is a tax credit for people paying college expenses. The maximum credit is $2,500 per student. For a married couple in a specific range of income, they lose $125 per student for every additional $1,000 of income. People with income below the phaseout range get the maximum credit. People with income above the phaseout range get nothing.

Suppose a married couple has two kids going to college in the same year. They would normally qualify for a $5,000 tax credit but they lose $3,000 of it because their income is in the phaseout range.

Their marginal tax rate is the normal rate from their tax bracket plus 25% but they still receive a $2,000 tax credit after losing $3,000. They pay $2,000 less in federal taxes than another couple with the same income whose kids don’t go to college. Higher marginal tax rate, yes, but lower total taxes in dollars. Getting a tax credit when your kids go to college (and presumably will have a better future) is great.

A similar effect exists in many other tax credits and deductions with an income phaseout, such as the child tax credit, the child and dependent care credit, the earned income credit, the saver’s credit, the student loan interest deduction, and so on. In each case, a higher marginal tax rate from losing some tax credits and deductions means lower taxes compared to others with the same income who don’t qualify for those credits or deductions due to other reasons.

Dividends and Capital Gains Bump Zone

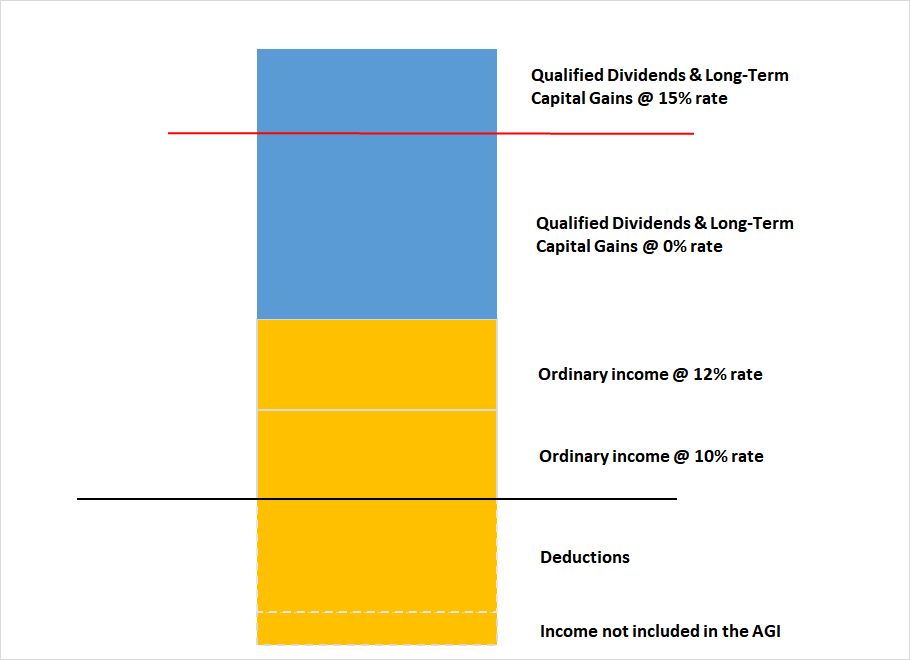

Michael Kites wrote about a “bump zone” in his blog post Navigating The Capital Gains Bump Zone: When Ordinary Income Crowds Out Favorable Capital Gains Rates. This happens when a part of your qualified dividends and long-term capital gains is taxed at 0% and the remaining part is taxed at 15%, as shown in this chart below:

The red line in the chart represents the cutoff point for the 0% rate on qualified dividends and long-term capital gains. It doesn’t move. The space below the red line is shared between ordinary income and qualified dividends and long-term capital gains taxed at 0%. As the ordinary income (the yellow part) expands, the qualified dividends and long-term capital gains (the blue part) are pushed upward by the same amount.

Any additional ordinary income will be taxed at the normal tax rate in addition to bumping an equal amount of the qualified dividends and long-term capital gains out of the 0% rate into the 15% rate. The combined effect is that the additional ordinary income is taxed at 25% or 27% instead of 10% or 12%.

Suppose a married couple has $40,000 of income taxed at ordinary rates plus $60,000 in qualified dividends and long-term capital gains. If they withdraw an additional $1,000 from their Traditional IRA, it’s taxed at 12% but it also bumps $1,000 of their qualified dividends and long-term capital gains out of the 0% rate to the 15% rate. Their marginal tax rate on this $1,000 of additional income is 12% + 15% = 27%.

Compare that to another couple with $90,000 of income taxed at ordinary rates and $10,000 in qualified dividends and long-term capital gains. If they receive an additional $1,000 in ordinary income, it’s taxed at 22% with no bumping effect because all of their qualified dividends and long-term capital gains are already taxed at 15%.

Both couples have the same total taxable income of $100,000. Although the first couple’s 27% marginal tax rate is higher than the second couple’s 22%, the first couple pays a much lower amount of total taxes in dollars because a big part of their income is still taxed at 0% after a small part is bumped out to 15%.

Again, a higher marginal tax rate means lower total taxes at the same income.

“Tax Torpedo” on Social Security Benefits

Retirees don’t pay federal income tax on their Social Security benefits when their income is low. As their income goes up and crosses a threshold, they start paying taxes on a part of their Social Security benefits. This works similarly to the bumping effect in the previous section on qualified dividends and long-term capital gains. Additional income is taxed at the normal rate plus it bumps another amount of the Social Security benefits out of the 0% rate.

It’s a little different than the dividends and capital gains bump zone in two ways:

1. The bump isn’t dollar-for-dollar. Each dollar of additional income only bumps 50 cents or 85 cents of Social Security benefits out of the 0% rate.

2. Social Security benefits can never be completely bumped out of the 0% rate. The maximum amount of the Social Security benefits that can be taxed is 85% of the benefits. The bumping ends when the maximum amount of the Social Security benefits that can be taxed is already taxed. At least 15% of the benefits will stay tax-free even if your income is $1 million a year.

The effect of this bumping is that for some Social Security recipients in a narrow range of income, their marginal tax rate on additional income is 1.5x or 1.85x of the normal rate. Some people call this the tax torpedo.

Suppose a married couple has $30,000 of income taxed at ordinary rates plus $50,000 in Social Security benefits. If they get another $1,000 from interest on their savings account, this $1,000 is taxed at 12% but it also makes another $850 of their Social Security benefits taxable. Their marginal tax rate on this $1,000 is 12% * 1.85 = 22.2% because they’re being “tax-torpedoed.”

Compare that to another couple with $80,000 of income taxed at ordinary rates who are not receiving Social Security benefits. If they get the same additional $1,000 from interest on their savings account, it’s taxed at 12% with no torpedoes.

Both couples have the same total income. Although the first couple’s 22.2% marginal tax rate is higher than the second couple’s 12%, the first couple pays a lower amount of total taxes in dollars. After taking on all the torpedoes, a part of their income stays tax-free.

Conclusion

Knowing your marginal tax rate is important for tax planning on things to do on the margin — making Traditional vs. Roth contributions, realizing capital gains, Roth conversions, etc. — but having an unusually high marginal tax rate doesn’t mean you’re paying high taxes. You’re not being penalized. You’re actually rewarded with paying lower taxes.

If you see people trying to rile you up by pointing to an unusually high marginal tax rate, they’re either misinformed or trying to mislead. What matters to your bottom line is the total amount of taxes you pay in dollars. We spend total after-tax dollars, not marginal tax rates. An unusually high marginal tax rate coupled with low total taxes in dollars sure beats a low marginal tax rate coupled with high total taxes in dollars.

If you find yourself with an unusually high marginal tax rate, don’t dread it. Celebrate. It means you’re paying lower taxes than other people with the same income. It also gives you bigger incentives to lower your taxable income and lower your taxes even further. You get much higher tax savings from your pre-tax contributions. Doing less work for a better work-life balance costs you less in after-tax income. It’s a great position to be in.

Learn the Nuts and Bolts

I put everything I use to manage my money in a book. My Financial Toolbox guides you to a clear course of action.

Coriander says

This is an interesting perspective, but in one major area I don’t think it applies – IRMAA, the income based surcharge on Medicare premiums. One additional dollar of income can push you into a higher IRMAA bracket, leading to a horrendous marginal rate and no lower tax rate to celebrate. That’s the real tax torpedo for retirees.

Harry Sit says

IRMAA is a surcharge for Medicare. If you see it as a tax, you would also consider the value of Medicare as a negative tax. Then it’s similar to getting phased out on tax credits. Many people would love to get on Medicare even at IRMAA rates to replace their inferior and more expensive health insurance.

JBo says

Your bump zone analysis is confusing. Adding $1000 income doesn’t change 0% rate? What am I missing in your math?

Harry Sit says

I added some explanation around the chart in the bump zone section. I hope it’s more clear now. If not, please read the extensive blog post by Michael Kitces linked in that section.

GJF says

Harry: You had me until your argument that a high marginal tax rate “gives you bigger incentives to lower your income and lower your taxes even further.” Lower income obviously means lower taxes, but it also means lower income. If, as you rightly say, “what matters to your bottom line is the total amount of taxes you pay in dollars,” then from a purely finanacial standpoint (putting aside quality-of-life considerations) wouldn’t it be better to pay more taxes as long as the after-tax income is greater?

Harry Sit says

I meant “lower your taxable income” as in making pre-tax contributions, as shown in the linked post for EITC recipients. Their taxes are already low or negative but they have a high marginal tax rate. They can make their taxes even lower or more negative when they make pre-tax contributions.

KjC says

Could you please explain the statement that “The maximum amount of the Social Security benefits that can be taxed is 85% of the benefits minus $4,200 for married filing jointly”? I just re-did the worksheet in the instructions for Form 1040, and it had me paying tax on 85% of my 2021 benefits. (Which is what I did when filing this year.) I must be missing something … please help.

KjC says

A follow-up: I am hypothesizing that the $4,200 comes from the $32K-$44K “layer” determining how much of one’s Social Security benefits are taxed.

12,000 * (0.85-0.50) = 4,200

But that has to do with the amount of one’s “provisional income,” not how much of one’s benefits get taxed. The IRS worksheet (and my tax-preparation software) still say the cap is 85%, period.

Thanks for any light you can shed on this.

Harry Sit says

You’re right. If your other income is high enough, it will overcome the 50%/85% tiering and the cap will be strictly 85% of the Social Security benefits. I edited the post to remove the $4,200 and $3,150. Thank you for bringing this to my attention.

Klaus Wentzel says

My wife and I are new to Medicare and we quickly learned that an extra dollar in income can cost you a lot in IRMAA. We also have a son in college, and found that an extra $20,000 can phase out the American Opportunity Tax Credit. I calculated that one can very easily push their marginal tax rate for that extra $20,000 you earn working a part time job above 60% after you add up FICA, IRMAA, loss of AOTC, State Income Tax, Federal Income Tax, and State Disability Insurance.

We are purposely trying to manage our income to avoid the tax traps. Your forecasting of IRMAA, Standard Deduction, and Tax Brackets is really helpful for our tax planning purposes.

You asked in your IRMAA post why the nickel and diming? My thought is that most people lack the Math skills or inclination to add up all their costs including taxes. The government is trying to hide exactly how much of your money they are taking. My wife and I try to educate young people that taxes are your biggest household expense and that it is a good use of your time to add up all the taxes you pay. We then encourage them to save as much as they can in their 401-K or 403-B to bring the tax number down.

Jonathan says

The Social Security “torpedo” is different because deferring or avoiding “other income” may allow part of the SS benefit to forever escape taxation. For example, if you’re going to get $50,000 in annual RMDs starting in 2024, this might cause $42,500 in SS (all of your benefit) to be taxed – if you’re in the 22% bracket, that’s 0.22*92500=$20,350 tax in 2024 and 2025 – a total of $40,700. But if you defer your first year’s RMD, then you’ll pay nothing – $0 – in 2024, and 22% on $142,500 = $31,350 in 2025. You actually save $11,150 in taxes!

Indexing and inflation will make the effect larger, and it’s possible that some of the larger income will spill into the 24% bracket, and you may have an IRMAA hit – but all of these are small compared to the tax saving.

Harry Sit says

If those are the only incomes, taxes aren’t calculated by simply multiplying the total income by 22%. The standard deduction and the 0% and the 12% tax brackets still apply. $50k IRA withdrawal plus $50k Social Security gives a total tax of $11,923 for a single person under the 2023 tax brackets according to a 1040 calculator I used. That’s $23,846 in two years. $100k IRA withdrawal in one year plus $50k Social Security gives a total tax of $24,276. Avoiding the tax “torpedo” makes you pay more taxes in this case.

If you’re talking about married filing jointly, it’s $6,121 x 2 = $12,242 over two years if you withdraw $50k from a pre-tax IRA and receive $50k in Social Security benefits each year. If you put $100k IRA withdrawal in the second year, you pay $0 in the first year and $15,871 in the second year. Once again, avoiding the tax “torpedo” makes you pay more taxes.

Jonathan says

The extreme case of Social Security and RMDs in that range being “the only incomes” may be unusual. Maximizing Social Security requires above-average income for 35 years. RMDs of $50,000 per year means at least $1.25 million in IRAs. A person with that profile probably has some significant interest and dividend income. The key point is that a 1.85 multiplier may apply to the Federal marginal tax rate for many moderately affluent people, and they might be in a position of paying that tax rate on income that could, with careful planning, forever avoid taxation. They should run a pro forma tax return, check on the SS taxation effect, and possibly take steps to avoid and defer income.

Harry Sit says

I agree with running a pro forma tax return but simply trying to avoid the Social Security tax “torpedo” isn’t the answer. Adding $10,000 interest and $40,000 qualified dividends and long-term capital gains to $50,000 Social Security benefits for married filing jointly under 2023 tax brackets:

$50,000 IRA distribution each year: Pay $12,372 x 2 = $24,744 in two years.

$0 IRA distribution in the first year and $100,000 IRA distribution in the second year: Pay $1,467 + $24,071 = $25,538 in two years.

Once again trying to avoid the tax “torpedo” costs money in this case. Are there scenarios that you could save money by avoiding the torpedo? I’m sure there are, but the point is don’t fall for scaremongering. Taking a hit by the torpedo isn’t always bad. Trying to avoid it can be counterproductive.

Jonathan says

I’m traveling and don’t have access to my tax software… You’ve run this for a relatively small SS benefit. Try using your numbers for a single taxpayer, or plug in the maximum SS benefit for a married couple of $109,320.

Harry Sit says

Bunching IRA withdrawals saves some money for a single taxpayer in this case but not nearly as much as one would think.

$50,000 IRA withdrawals each year: Pay $20,816 x 2 = $41,632 over two years.

$0 IRA withdrawal in the first year and $100,000 IRA withdrawal in the second year: Pay $8,674 + $32,676 = $41,350 over two years. Bunching saves $282, which is less than 1% of the taxes paid.

By now we have seen enough of this to conclude that trying to avoid the “torpedo” is a hit-or-miss. Sometimes you save some money by working around it. Sometimes you end up worse off. It depends on one’s filing status and the income size and composition.

Jonathan says

As I said, I’m traveling, and it’s tricky to do this on my phone, but I found an online tax calculator at https://turbotax.intuit.com/tax-tools/calculators/taxcaster/

For a single person receiving $53,000 year in Social Security benefits and $10,000 in other income, then here are the tax bills with IRA distributions:

0: $194; 50000: $15,526; 100,000: $27,520

194+27520=27714. 2*15526=31,052. Delaying the first RMD saves 31052-27714=$3,338 in tax.

For a married couple receiving the max of $109,320 in SS with 20,000 of other income, we have these tax amounts for 3 distributions:

0: 6,755; 50,000: 27,473; 100,000: 40955

40955+6755=47710. 2*27473=54946. Delaying the RMD saves them 54946 – 47710 = $7,236.

These numbers rely on the tax calculator correctly computing the taxable amount of the Social Security benefit.

Harry Sit says

That online calculator is still on 2022 brackets but you’ll see the same effect when you add $40,000 in qualified dividends. Bunching works for some ranges and compositions of income but not others.