Princeton University professor emeritus Burton Malkiel and the author of the popular book A Random Walk Down Wall Street wrote in the Wall Street Journal The Bond Buyer’s Dilemma. Professor Malkiel suggested some reasonable alternatives to long-term U.S. Treasuries.

“The first is to look for bonds with moderate credit risk where the spreads over U.S. Treasury yields are generous.”

Professor Malkiel gave muni bonds as an example for this. I agree.

Yes muni bonds have more risk but the spreads are generous. Pension funds and foreign governments don’t get the tax advantage from investing in muni bonds; individual investors do. When we as individual investors buy muni bonds, we get a break because we are not competing with pension funds and foreign governments.

For this reason, I hold muni bonds in my taxable account and value stocks in my tax deferred accounts. See previous post Dividend Tax Going Up, Moving to Munis.

Professor Malkiel then suggested close-end funds that invest in muni bonds with a leverage. I don’t think we need to go that far. Leverage increases risk. High management fees in close-end funds also take away some returns. Plain-vanilla muni bond funds will do.

Professor Malkiel also suggested

“Another class of bonds that is attractive today is foreign bonds in countries that have much better fiscal balances than we have in the U.S.”

He gave Australia as an example.

“High-quality Australian private bonds are available at yields of 8%.”

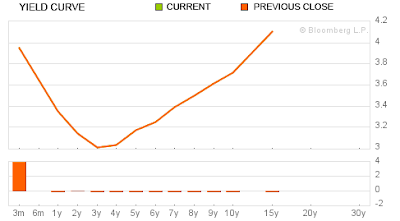

I’m not sure what high-quality Australian private bonds he’s talking about. Note the word “private.” It sounds like corporate bonds, not Australian government bonds. I don’t know how private bonds have anything to do with a country’s fiscal balances. Bloomberg shows yield on 10-year Australian government bonds is 3.7%, higher than the 1.9% yield on 10-year U.S. Treasury, but nowhere close to the 8% number Professor Malkiel mentioned.

I don’t have a good explanation for why Australian bonds would yield that high. I assume the market knows something I don’t. Maybe it’s forecasting that the value of the Australian dollar will fall.

I’m taking a pass on this one because I just don’t know enough about foreign bonds that yield higher. Yield on a more diversified foreign bond ETF, for instance SPDR Barclays Capital International Treasury Bond ETF (ticker BWX), is only 2.5% with a duration of 7 years. It’s not that much higher than the yield in the U.S.

Finally, Professor Malkiel suggested

“Another strategy would be to substitute a portfolio of blue-chip stocks with generous dividends for an equivalent high-quality U.S. bond portfolio.”

Here, I both agree and disagree with the suggestion. With a low bond yield, I think a reasonable case can be made that stocks will have a higher return than bonds. Therefore increasing the allocation to stocks will increase a portfolio’s return.

During late summer early fall when stocks went down and bonds went up, I rebalanced from bonds to stocks. It worked. Stocks rebounded, not completely, but enough to beat the return in bonds.

However, will “blue-chip stocks with generous dividends” be better than other stocks? It’s not that clear. Dividends give you the comfort you are getting something, but it’s the total return that counts. I would focus on total return, not just dividends.

In his article How to invest in a low-interest-rate world, investment advisor Larry Swedroe agreed that muni bonds are a better bet but he disagreed with Professor Malkiel on foreign bonds and high-dividend stocks.

Investment advisor Allan Roth also disagreed with Professor Malkiel. His solution is FDIC-insured CDs with low early-withdrawal penalties.

I’m with Allan Roth on this one. If you are holding bonds in a tax deferred account, you are better off with FDIC-insured CDs. The good CDs have a higher yield than Treasuries. They have a similar yield to investment grade corporate bonds but at a lower risk. They also have a lower interest rate risk than both Treasuries and corporate bonds. What’s not to like?

Once again, we as individual investors are better off with CDs because we don’t have to compete with pension funds and foreign governments.

The same is true for I-Bonds: no competition from pension funds and foreign governments. Fixed rate is stuck at zero when short- and intermediate-term TIPS yields go negative.

In summary, here are my solutions to the bond buyer’s dilemma:

- FDIC-insured CDs in tax-deferred accounts (PenFed, Alliant CU, Ally)

- I-Bonds in taxable accounts (TreasuryDirect, $10,000 per person, including buying with tax refunds)

- Muni bond fund in taxable accounts (Vanguard)

- Buy more stocks when prices are low

Learn the Nuts and Bolts

I put everything I use to manage my money in a book. My Financial Toolbox guides you to a clear course of action.

LES says

A great time to ‘step down the ladder’ again with a no-cost mortgage refinance.

Harry Sit says

@Les – Yes, although I haven’t seen anything that beats the 5/1 ARM at 2.625% I got last summer. PenFed’s 5/5 ARM is still at 3.25%, same as in the summer. 30-year fixed rate is down about 0.25%; 15-year fixed down about 0.5%. It proves once again stepping down the ladder with a no-cost loan is the right approach. Those who paid closing cost and/or points wasted money.

enonymous says

Hmm, a man by the name of Markowitz would disageree with much of this post.

Unless you think Modern Portfolio Theory is bunk (and perhaps you do, or it is) and mean variance optimization is a flawed concept.

How a portfolio functions is more than just the sum of its parts. I like CDs, I like Munis, I like I bonds, but none of them pay you for capital appreciation/ price improvements due to flight to safety/quality.

Over the past year (2011 ytd) medium to longer term US treasuries and TIPS both have returns of right around 15% (vs -2 to -15% for various equity classes). That is in spite of yields of <2% nominal (and 0-1% real). So the question is, woudl you rather have 30% of your protfoli in munis, or Cds, or I bonds, which offer better yield, euqivalent or worse credit risk, but no price appreciation (or depreciation)? I can't predict the future, but I do realize that comparing instruments of similar duration and credit risk based simply on yield is a mistake.

Similar duration CA munis this year have lagged US treasuries slightly this year. CDs, of course, have a great put option, as do I-bonds, but have lagged badly.

Next year might be the opposite – who knows? But looking a coupon of the instrument in isolation is a mistake, IMHO.

enonymous says

oh, and I agree with Les – I’m doing 3.25 on a 15yr fixed, no cost, yet again

Harry Sit says

enonymous – If two instruments have similar duration and credit risk but one yields higher than another, the higher-yielding instrument will have the same capital appreciation due to flight-to-safety, not all in one-shot, but over time. Unless you are a trader, the capital appreciation up front eventually wears off over time.

Suppose at this time last year there was a 30-year CD and a 30-year Treasury and the CD yield was higher. One year later your 30-year Treasury gained say 20%. Let’s say you can’t sell the CD at a 20% premium. Are you better off with the Treasury? No, because over the next 29 years, your CD will earn that 20% back slowly via its higher yield.

enonymous says

I’d disagree with quite a bit of your response

You may or may not believe in the ‘rebalancing bonus’ – if you do then the flight to safety/liquidity benefits of US nominals are especially signifcant. If you don’t, it is also a fact that the likely negative correlation (not always the case, but likely the case) of USTs function to decrease the sharpe ratio of a protfolio, all else equal.

Of course, munis are not judged to be of equal credt risk (perhaps this is a mispricing) and they definitely do not have equivalent liquidity. CDs are equal if not better credit wise, but their liquidity is very poor.

I’m not arguing that munis or CDs are bad – simply that in the context of an entire portfolio, especially if dominated by equities, munis and/or CDs may not be better than USTs, as they might first appear based on yield alone.

In 2009 US nominals funded my large rebalancing purchases of equities. Munis would have failed (and they did) to provide that timely ‘protection’ CDs, depending on their liquidity, may or may not have worked.

For the record, I do hold a few munis, and 5% 10 yr CDs in a 529. If yields were sufficiently high, I would consider either instrument. Right now I’m reminded of that old line though More money has been lost chasing yield than at the point of a gun…

Harry Sit says

enonymous – First of all, it’s not all or nothing. You can certainly keep some Treasuries for rebalancing purposes. Does it have to be the bulk of your fixed income? How much do you sell in a rebalancing move? Maybe 5% of the portfolio or 15% of fixed income? Keep double that amount. That’s plenty already. The rest, 70% of fixed income, can be kept in less liquid instruments, earning a liquidity premium. Second, you can’t eat Sharpe ratios. If you keep more than you need for rebalancing in US Treasuries and you show your superior Sharpe ratio but have less in absolute dollars, I don’t know what that does exactly.

enonymous says

ah yes, the old ‘you can’t eat risk adjusted returns’ line.

absolute dollars are the the key, of course, but especially those nearing or in the drawdown period, volatility can cause serious issues – and you can’t eat a crummy CAGR that is the direct result of a bad sequence of returns. The Sharpe ratio matters for a number of reasons – the biggest one being behavioral reasons (rational investors are few and far between), but it also matters because otherwise, it would be appropriate to devise a low Sharpe ratio, high expected return portfolio (eg 100% levered EM). for obvious reasons, expected returns are just that, and the ERP is a consequence of the inability to know whether these returns will actually materialize. So yes, a high rate of absolute return is the key, but viewing it in a vacuum of the risk taken to achieve those returns does not square with financial prudence.

I’d agree it does not need to be all or nothing. The issue I took was with the following:

In summary, here are my solutions to the bond buyer’s dilemma:

FDIC-insured CDs in tax-deferred accounts (PenFed, Alliant CU, Ally)

I-Bonds in taxable accounts (TreasuryDirect, $10,000 per person, including buying with tax refunds)

Muni bond fund in taxable accounts (Vanguard)

Buy more stocks when prices are low

none of it is bad advice, and it may well be correct. There are numerous issues with your bullet points as well – I hope I’ve highlighted a few.

Harry Sit says

I did say those are my solutions, right? I’m not in distribution. Sequence of returns doesn’t affect me much. The four bullet points largely play on iliquidity. I’m a patient investor. I don’t have skittish investors knocking on my door demanding their money back at a moment’s notice. I don’t need all my money completely liquid at all times. Therefore I can afford to invest in CDs that are less liquid. I don’t calculate my Sharpe ratio. We are talking about CDs versus Treasuries here, not levered EM.

enonymous says

I agree with most of what you said, and I don;t calc my Sharpe rato either 🙂

My point is simply that the concept is still valid. Let’s say you knew, or believed that 100% EM has the highest expected return of any asset allocation. Let’s say you are a robot, and able to avoid any irrational investor behaviors. Then let’s say I give you the choice of improving your Sharpe ratio with one investment vs the other, assuming equal reduction in absolute returns. Why wouldn’t you choose the higher Sharpe ratio? After all, you can’t eat the better risk adjusted returns (assumpton is absolute returns are equal), so who cares?

Well, even the robot cares, because the expected returns are only expected. It is always preferable to achieve the same absolute returns with lower volatility. That’s the whole basis of MPT. I agree getting paid to be illiquid is a beneift fo being a patient retail investor. It’s just that sometimes you get paid less than it is worth – and sometimes your portfolio will do better as a reusult of selling the liquidity premium to others who need it when you need it least. TIPS in late 2008 were a perfect example…

Vikram says

Hi – What would you think abt this Vanguard Bond Fund for the next couple of years of low interest rate –

VWESX

Harry Sit says

Vikram – VWESX = Vanguard Long-Term Investment Grade Fund. No I wouldn’t be comfortable with it for the next couple of years. Big mismatch between “long-term” and “next couple of years.”