Over the Thanksgiving holidays a friend asked me whether he should buy whole life insurance. He said an acquaintance had been pitching him this whole life insurance policy as a better way to invest in fixed income. The idea is it has no risk from the stock market and it’s tax free.

I told him he shouldn’t buy it but he still asked me to look at the details in the illustration he received from the life insurance agent. The illustration is for a Whole Life Legacy 10 Pay with Life Insurance Supplement Rider (LISR) from MassMutual. It runs over 30 pages, full of numbers and unfamiliar terms to my friend. I really don’t understand why anyone wants to torture him- or herself with such a document. Maybe that’s the point of the document. When there are so many numbers, you don’t know which ones to look at. You are left with the agent’s narrative: tax free and no risk from the stock market, which are both true and misleading at the same time.

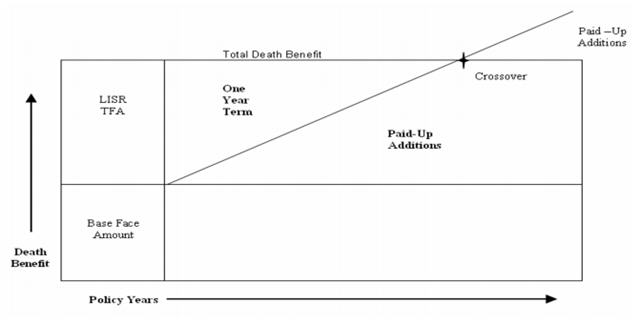

Because my friend doesn’t really need extra life insurance, he’s only interested in using it as a tax-free investment vehicle. The policy is structured as a blend of whole life and declining one-year term life insurance. As far as I can tell, it’s designed that way to get around the IRS limit on how much money you can put into a life insurance policy up front and not make it a Modified Endowment Contract.

I was able to point out to my friend that the “total cash value” column was the most relevant numbers to him among pages and pages of numbers in the illustration. The most revealing number is the total cash value after one year. After he pays $30,000, if he decides to get out at the end of one year, he would get back only $24,000. What would cause the insurance company to suffer such a loss to the tune of 20% in just one year? It doesn’t cost $6,000 to insure against death for only one year. That $6,000 for the most part goes to the insurance agent. No wonder the insurance agent was pestering him to buy the whole life policy!

Low Returns

An Internal Rate of Return calculation using a spreadsheet shows the 10-year average rate of return would be 0.9% per year guaranteed and 2.9% per year non-guaranteed. Non-guaranteed is just an estimate. The actual return could be higher or lower. Considering that my friend can buy a 7-year CD at a 3% yield from Andrews Federal Credit Union with government insurance, I don’t see any point in locking in the money longer AND earning less.

Holding the policy longer gets a little better. The 20-year average rate of return would be 2.5% per year guaranteed and 4.5% per year non-guaranteed. Nowadays even simply buying a 20-year Treasury would get you a return of 2.7% per year. It makes the 2.5% guaranteed return from the whole life policy a moot point. Corporate bond yields are higher than Treasury yields. Fidelity shows me several AA-rated 20-year corporate bonds with yields at about 4%. Who knows whether the 4.5% non-guaranteed return from the whole life policy will materialize or not.

Source of Low Returns

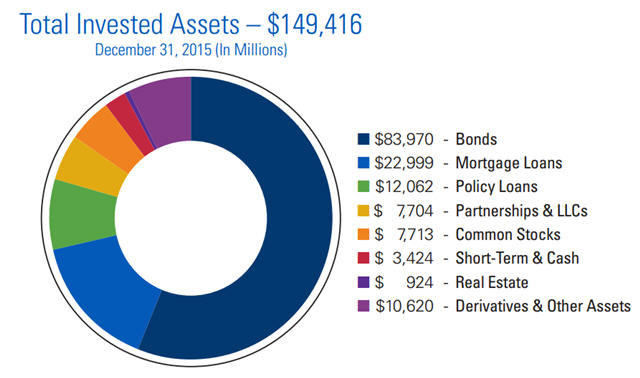

How come you are getting only bond-like returns even when you invest with the insurance company for 20 years? Just take a look at the balance sheet of the insurance company. After all, money does not grow on trees. The insurance company can only give you what they make from investing your money after taking out their expenses. This chart from MassMutual’s annual report shows the breakdown of its invested assets:

If you add up bonds, mortgage loans, policy loans, and short-term & cash, they make up 82% of the total invested assets. You are getting bond-like returns at best because the insurance company itself invests in bonds for the most part.

Tax Free

A major selling point from the insurance agent is that the whole life policy is tax free. It’s true, but it’s not what you think. The increase in cash value is tax free, but you can only stare at it. If you get satisfaction from only looking at larger and larger numbers but you never use the money in your life, it’s indeed tax free. Your beneficiaries will get the money. It’s not that simple if you yourself actually want to use the money.

You can take tax-free loans from the insurance company using the cash value as your collateral. Taking loans isn’t free. Instead of paying taxes to the government, you pay interest to the insurance company. You pay taxes only once when you get the money. You pay interest every year when you have a loan. If you take loans and you pay interest year after year, you may be worse off than just paying taxes.

The illustration shows a scenario with taking out tax-free loans. The rates of return with tax-free loans are worse than the rates of return without loans.

| Without Loans | With Loans | |

|---|---|---|

| 10-year non-guaranteed average annual rate of return | 2.9% | -1.7% |

| 20-year non-guaranteed average annual rate of return | 4.5% | 1.9% |

What does -1.7% per year return for 10 years mean? It’s equivalent to investing $10,000 at the beginning and getting back only $8,400 after 10 years. You are supposed to grow your money and beat inflation. Now you are losing money even before inflation. One must be crazy to want to do that. Even the -1.7% is non-guaranteed. It could be worse. If you invest for 20 years, is 1.9% per year with tax-free loans really better than 4% taxable from just buying a corporate bond?

Tax free is good, but not if you get a worse return than just paying taxes.

At this point insurance agents will come out and say this policy isn’t structured properly or it isn’t sold properly. Somehow the improperly sold policies are always done by other agents but they themselves have the magical properly structured policies that do wonders.

Come think of it, thinking there is magic led my friend down this path of getting pitched the whole life policy. We need to stop looking for magic. See Why Do People Buy Snake Oil?

Learn the Nuts and Bolts

I put everything I use to manage my money in a book. My Financial Toolbox guides you to a clear course of action.

Park says

Harry – love your detailed yet clear & accessible look at this option!

I work for a direct competitor of the firm mentioned here and think this is exactly what AGENTS DON’T WANT CUSTOMERS TO SEE… clear description of how such products frequently give purchasers worse results than they can easily get elsewhere and fatten the agent’s (and their firm’s + backing multinational’s) pockets.

Bravo for putting this out there. Have never commented before, but felt compelled to do so after seeing this.

In similar vein of shady tactics, you should also look at the industry’s pushing of 403(b) plans to educators (check out NYTimes’ series of pieces on the topic earlier in October 2016).

Eric Gold, MD says

A classic.

Harry, if this does not cement your reputation as the best personal finance blog, nothing will

Sam says

Agree. TFB & Harry Sit = the best personal finance blog!

Stephen L Nelson CPA says

Harry said, “…I really don’t understand why anyone wants to torture him- or herself with such a document. Maybe that’s the point of the document…”

I believe this is exactly the point of these ridiculously complex products. They are so hard to understand, basically no one can size them up without a lot of effort. Heck, some people even with a lot of effort can’t size them up…

Great work, Harry ! Thank you.

Andrew Michaels says

You should read “Confessions of a CPA: The truth about life insurance” by Bryan Bloom. It’s an eye opener for CPAs with detailed knowledge about how these products work and how they benefit clients.

The author should as well before putting either biased or uninformed pieces out there like this one.

Eric Gold, MD says

My rule of two thumbs:

1. Read the contract

2. If I cannot fully understand the contract, don’t sign

The White Coat Investor says

Getting $24K of $30K back after a year is actually really good. Must be some paid up additions and some reasonable structuring to the policy. The typical commission on a vanilla policy is 50-110% of the first year’s premium. So I expected a 1 year cash value more like $5,000!

But you’re right, the returns on whole life policies, even when kept for decades, are not good. Most of the vanilla ones I look at guarantee a return of about 2% (after 50+ years) a year and project returns in the 4-5% range. So I’d expect something like 3-4%. Seems silly to me to tie up money up for so long for such terrible returns especially when the short term returns are even worse.

The tax-free thing is a bit of a scam. You can borrow against ANYTHING (your home, your car, your insurance policy, your firearms) totally tax-free. But it’s not interest-free. So that’s not some magic thing about life insurance.

Harry Sit says

The high face amount of the LISR in the initial years allows more funding up front. The premium for the base coverage is about $6k a year, which my friend would lose after one year.

Art says

Is everyone forgetting that this is LIFE insurance and the company would have to pay out

the death benefit whenever the client dies, even if he only paid one month of premium!

How much does that CD pay if the client dies after one month?

Harry Sit says

How much does term life cost? It also pays the death benefit if the client dies after one month.

Smart Money MD says

Great summary and clear layout of the cons of WL. If there’s any positive in this is that it does look like the policy is written to have you maximum the amount you put in and shorten the number of years needed to break even.

My brother has a WL policy that was sold to him, and I believe that at year 5-6, he’s still in the negative.

Mark Schroeder says

Good points on the article. That policy is actually designed better than most I have seen. That said, rarely is the interest talked about and how that impacts the plan which is a great point.

The only negative of the article in regard to retirement planning is that it focuses simply on accumulation of assets and not distribution. Whole life can be very valuable down the line as an asset allowing for higher retirement distribution amounts vs just investments especially taxable ones.

Harry Sit says

It focuses on both. Whole life does not allow for higher retirement distribution because (a) you won’t have as much to distribute from to begin with; and (b) if you do tax-free policy loans you pay interest. This combination makes you worse off than just paying taxes.

Mark Schroeder says

I think it does help because I see it with my father.

Actuarial science says you can take out about 3% today for 30 years of retirement out of investment accounts. If someone has whole life cash value that is guaranteed to go up they can take 6-8% out of their investments…and if they have a pension or annuity they can take the much higher life only payout.

3% of 2 million is 60k year from investment

6% of 1.5 million is 90k a year from investments. If investments drop you can leave them on the market and take out of whole life.

Harry Sit says

It’s not true you can only take about 3% today out of investment accounts. How old is your father? I just went to immediateannuities.com. For paying $1 million today, a 65-year-old male can get $5,532/month for life. That’s 6.6%.

Mark Schroeder says

He is 69….i guess you could say 4% even though that number is in a different time of interest rates.

I don’t want to argue for the sake of arguing but there is an unwarranted amount of hate for a steady product in whole life from a participating non direct recognition company.

Markets go up and down. People become more conservative when they are older. If they have a portfolio with a good whole life product they can stay 100% In equities if they want and should average higher than the average investor.

Sure vanguard s&p investor may accumulate more than an investor who also has whole life. But retirement income is just as important as accumation. I would rather be able to have higher distributions and a guaranteed product in retirement than worry about the market or have ladder bonds.

Everyone is entitled to their opinions but to say this contract is a terrible thing to do is not necessarily accurate. Especially since we don’t know the future.

Harry Sit says

Are you in the insurance business? I have never heard of any regular consumer outside the insurance business use the term “participating non direct recognition company.” You see I didn’t compare whole life to the stock market at all, only corporate bonds and CDs. The world isn’t made up of either S&P or whole life in that if you don’t want to be 100% in S&P you must put some in whole life. One can invest in corporate bonds and CDs instead of whole life. Corporate bonds and CDs are also steady and guaranteed; they are guaranteed by the bond issuers and FDIC. Investing in corporate bonds and CDs also allows one to invest the rest in the stock market.

Maybe your father had good returns from his whole life policy. It’s only because back then interest rates were high. Rates were above 10% in early 1980s. If he invested in corporate bonds and CDs instead of whole life he would’ve done even better.

Just like you can’t invest in corporate bonds and CDs today at much higher rates available in the past, you can’t invest in whole life today and receive returns of the past. The balance sheet chart shows investing in whole life is a convoluted way of investing in mostly bonds held by the insurance company. If interest rates go back up and whole life will deliver good results, so will investing in corporate bonds and CDs.

Rosemary says

Would rather have 1 million. With SS, $5,000 a month and 401K etc you may be paying much more for Medicare. A million dollars now could pay for grandchildren’s college and do other things to help others.

Steve says

I agree, if they are equal anyways, I’d rather have the liquid cash.

Matthew Heaney says

I agree with Harry, there is no reason to be buying whole life insurance (see the many articles over at White Coat Investor why whole life is a terrible idea). Invest your money in some combination of stocks, bonds, CDs, TIPs, and annuities.

Greg says

Stocks bonds and annuities. Ever here of the Infinite banking concept?

DHK says

I have a 25-point checklist comparing life insurance to 401(k)/IRA, Roth IRA, 529 plans, and brokerage accounts. Life insurance comes out on top. Not on all points, but on the vast majority of them.

Harry Sit says

Just one question: do you sell life insurance? It’s hard to understand something when your livelihood depends on your not understanding it. Only sellers make 25-point checklists.

DHK says

Of course I do. But your statement is odd – but I do understand that English is not your first language.

My livelihood depends on not only MY understanding of it, but in making this complicated product SIMPLE for others to understand it, so they can take full advantage of it. But they CAN’T take full advantage of it… if they aren’t advised by someone who knows HOW to take advantage of it.

The advisor is the key. Correction: the licensed advisor who can be held accountable for his recommendations AND has a financial interest for keeping the policy placed with those he sells… is the key.

You see, if the client isn’t happy with the product, they return it and it causes commissions to be charged back against the agent. If the client REALLY isn’t happy, they can complain to the insurance company, state department of insurance, and other regulators. If the agent/advisor “over-sells” the policy by selling a policy that they can’t afford… will cause problems too.

And for some reason, you believe that those who “sell” should be demonized. I don’t “sell” in the traditional sense, but I do consult. I present the ideas, and my prospects buy from me – with full disclosure of how the product works.

Steve says

If your using whole life as an investment tool then you’ve got it all wrong. Whole life was meant to be a buffer asset. Whole life should be used as like an emergency fund. Whole life is a financial tool not an investment tool. Harry is right about everything he said but going with a mutual company such as MM or NYL or NWM you have more security then being in the market and bonds or CD because interest rates effect those vechiles much more then whole life policies. I’ve suffer from 2008-2009 and barely getting the money I’ve lost back and this is all through an aggressive 401k. Luckily I have 3-4 different financial vechiles to chose from when I want to make my withdraws.

David says

Except that Harry is not right about everything (which is fine, or course).

These kinds of articles always bothered me because they start with a premise that can never be true and then the author has to do backflips to “prove” the point.

In this case, Harry writes that most of the $6,000 differential goes to commissions. How does he know this? Mass Mutual’s LISR is a low-premium supplemental term policy and Mass allows a large multiple of the base face amount as term insurance so the total payable commission is low — unreasonably low in my opinion. Unless the agent did something very unusual (in which case, why bother using a blend?), he or she isn’t being paid very much for this design.

If his friend canceled his insurance policy in the first year, it’s true he would not get back the full $30,000 premium. Why would he? There are underwriting and operating costs that have to be paid. He would likely get a premium refund credit (which is common in the industry) since he didn’t have the insurance for the full year. Insurers can only accept premium for insurance coverage.

You don’t pay 12 months premium and only recieve 6 months coverage, for example.

But, let’s suppose his friend tried this in an IRA. Assuming he could put in $30,000 to begin with (which he can’t), how much does his friend get back if he decides he doesn’t want to do this anymore after 6 months? He gets his principal, plus investment gain, minus the 10% penalty and minus taxes. Maybe it costs him $10,000.

Buyer’s remorse is not free.

He also states friend doesn’t need any more insurance. But, insurance companies will not overinsure an individual for onvious risk and liability reasons. Maybe his friend doesn’t *want* more insurance. OK, fine, but that’s different and the tone of that statement is different.

Harry also chooses to compare the return on cash value to a 20- year Treasury. Whole life cash values compound. CMT rates do not. Additionally, even though you could theoretically reinvest all interest payments in new issues, you take on additional risk this way. And, as the interest rate moves, the value of your bonds changes. Rising rates aren’t going to make Treasuries a “slam dunk.”

Does that really make the returns on whole life a moot point?

Harry’s smart enough to know the difference considering his excellent series on TIPS and other investment ideas.

The rest is just a tired narrative.

Mark Zoril says

What an excellent post! Finally got around to reading it.

Craig says

Great post, however . . .

I am trying to decide now whether to get a whole life policy. I’m 37 and have a child with special needs; part of the need for life insurance is to fund a special needs trust while I am young and have not yet built up sufficient wealth on my own to care for my child for the rest of their life. So from my perspective, your comparison (bonds/treasuries/other investments to whole life) is not the entire story. I am deciding how to allocate money among investments and life insurance, which is a necessity in my case. So I have to decide between term life and whole life. It’s not clear to me at all what the best combinations are. I can invest everything, but that leaves the trust severely underfunded for ~20 years. Or I get some term, which funds the trust, takes money out of investing, and allows me to build wealth in the interim. Or I can get some whole life (or a version of universal life), which can also serve as an immediate funding of the trust and build wealth slowly itself (or, as with UL, be around forever). Or a combination of the two. So which is better, pay a third of the price or so for term, and have nothing at the end of the term, or pay for whole life and have something at the end. That’s the only real choice for many people.

Harry Sit says

“Nothing in the end” is simply the wrong way to think about it. Any insurance, when the insured event didn’t happen, will not give you anything in the end. When your house doesn’t burn down, you don’t get anything from the insurance company, but you still have your house. When you buy term, and you don’t die at the end of the term, you have everything else you invested in during the term: your retirement accounts, a 529-ABLE account for the child, your investments, your home, … They are all available to your child when you eventually die.

Craig says

I didn’t mean to exclude opportunity costs. It’s just not clear to me at all whether term, UL, or whole life is best for my situation. Term plus investing the difference is a good option, undoubtedly. But perhaps I should spend more for a UL policy if I would simply renew term life when I’m 57. Either way, I’m leaning against whole life.

Harry Sit says

The “money doesn’t grow on trees” principle simply says after covering the risk of your premature death, whatever the insurance company makes available to you can only come from investing the extra premium. When you see the insurance company’s investments, consisting of largely bonds, you know the returns can only be what those bonds return, after subtracting the insurance company’s cost structure. I don’t see how UL would make any difference. If you’d like to invest in bonds, after buying term, you can invest in bonds yourself. You don’t need to go through an insurance company. So figure out when your investments will grow to a point that will cover your child’s needs even after you die, then buy term to cover yourself to that point.

You don’t have to renew your term at 57. If your investments need 30 years to grow to a size large enough, buy 30-year term to cover yourself to 67.

Craig says

I’m going with 20-year term policies. I have a couple 10-year term policies that will expire over the next several years. As they expire I may add some more 20-year term. The 30-year term is nearly twice as expensive, so I’d rather have more coverage early on. My earning potential is increasing and savings growing, so my need for insurance will definitely decrease as I age.

Thanks for helping quiet any doubts in my mind.

Steven Caban says

This is a highly skewed analysis and try’s to make apples to oranges comparisons.

1. You disregard non-guaranteed returns as if they rarely materialize. When many reputable companies have a decades long track record of paying non-guaranteed returns every year.

2. These returns are not taxed on interest if you pay up additional life insurance with the proceeds.

3. You absolutely NEVER look at short term returns when looking at whole life. It’s not a short term vehicle and wasn’t meant to be.

4. When people cancel their policies the insurance company can record that as profit, which ultimately is what gets paid out to policyholders as non-guaranteed returns.

5. Hence when you cancel your policy you make other people wealthy. Using statistics we can predict how many policyholders will cancel in a given year.

6. You discount entirely the fact that there is a guaranteed death benefit if you die prematurely. CDs do not. Again apples to oranges.

7. The flexibility of having an ever increasing death benefit while still having the flexibility to cash out tax free in your later years is not touched on either.

8. Some of these comments are obvious Financial Planner shills probably pitching front loaded mutual funds so virtue signaling about commissions is pathetic.

Meredee Grant says

Thank you Steven Caban for your comments above. People want to constantly vilify Whole Life Insurance Plans but they don’t remember that eventually, as long as you keep paying, you will die and your beneficiaries will get the proceeds, guaranteed!!!! That means a lot to the people who inherit the money. Why isn’t that figured into the returns.

I have a question for you, my whole life insurance agent told me that if I take out a loan against my cash value I would be paying interest but that interest would just be put back into my account. So, essentially, I would be paying myself interest. I’ve heard this before but it sounds too good to be true. Also the comments above don’t say that at all. What is the truth?

Harry Sit says

Only those who sell whole life policies tout them. If you keep buying anything, stocks, bonds, CDs, real estate, your beneficiaries will also get the proceeds when you die. Money does not grow on trees. When you see insurance companies invest largely in bonds you know the returns will come from those bonds. Bond yields were above 15% in the 1980s. Of course returns were good in the past. But we are talking about buying now. Who sold policies to those who canceled and made other people wealthy? Statistically you have a good chance to be one of them, but you can believe you are above average like everyone else does.

Steven Caban says

Meredee – You should ask your agent for those illustrations.

Harry Sit – “Only those who sell whole life policies tout them.”

And a those who sell Subarus tout Subarus. This comment doesn’t contribute anything. Furthermore, many Life Insurance agents hold securities licenses, they are agnostic to the instruments used.

If you can’t look someone in the eye and ask him what would happen to their loved ones if he died, you are not giving your client the financial foresight they need.

That’s why life insurance comes first, investments second. Its the Golden Goose concept. Someone’s life is the number one income producing asset they have.

“If you keep buying anything, stocks, bonds, CDs, real estate, your beneficiaries will also get the proceeds when you die.”

When you buy life insurance you insure your ability to generate income. You don’t generate income after you die. So who is going to pay your mortgage and invest in stocks?

“When you see insurance companies invest largely in bonds you know the returns will come from those bonds.”

Your reductionist attempt doesn’t hold water. Saying ‘insurance companies mostly invest in bonds hence you are just overpaying for a bond fund’ ignores what an insurance policy actually is and how returns are paid out. It’s not just based on bond yields as you are insinuating.

“But you can believe you are above average like everyone else does.”

And you can believe that people don’t die and don’t need life insurance.

Steve says

Steven Caban: selling someone a whole life policy is likely to leave them underinsured. Early in their career, they have the most earnings ahead of them, but at the same time (and in fact for the same reason) they don’t have much money currently. Term life gets them the most insurance for the least money.

By the time someone has enough spare money to buy an adequate whole life policy, they likely have a reduced need for insurance.

Harry’s comments about investing in stocks, and how insurance is effectively investing in bonds, is refuting Merdee’s comments that your heirs will get the money sooner or later.

We all die; that is inevitable. You can’t insure something inevitable. Term life insurance protects against the risk of dying earlier than average. (Annuities are one way to protect against the risk of dying late.)

Craig says

I am young with only a modest net worth now, but very significant life-long earning potential. Having spent quite a bit of time thinking about the best option for my family, it’s a no-brainer. As others are saying, term life insurance is exactly the product that is best suited to my situation. I can buy more of it than I can whole life. That means, my family will have greater security during the time we need it most–if I die young. The need for that security diminishes over my lifetime. So the extra cost for whole life is not justified, particularly when, as yet others have said, the returns are so low.

Whole life is upselling, pure and simple.

Steven Caban says

Steve – No doubt Term life will give you more protection over the long term. You are setting up a straw man argument by assuming I would recommend a whole life policy to someone who needs a term.

Craig – Agreed, for a young person with children to take care of Term life is definitely the option.

Whole Life is better suited with someone who is already settled into their career, and already has the Term protection then need for their biggest liabilities.

The guaranteed returns and the dividends for whole life are quite high with many of the top carriers hovering over 6% dividends on average. I wouldn’t consider that “low” for such a safe vehicle. Stock returns haven’t been that impressive, averaging 8.5% in the past 20 years BEFORE fund fees.

I don’t agree that Whole Life is upselling pure and simple. But it can be upselling from the wrong agent.

Harry Sit says

Creating false choices is a neat trick. When whole life isn’t the only way or the best way to offer protection, what does looking someone in the eye or someone’s life being the number one income producing asset have to do with buying whole life? 6% sounds good. 6% on what and when are the questions. Is it 6% on the entire premium or only part of it? Is it 6% in the past or 6% in the future? It’s easy to guarantee or pay 6% when you have bonds that paid 10%. Thank you Steven Caban for demonstrating these false argument tricks. We need more of them.

Steven Caban says

Harry Sit – False choices? I’d rather not answer these loaded rhetorical questions. You should do your research into how insurance companies make money and how they can pay policyholders dividends on a profitable loss ratio. I’d be curious to know if you ever earned your Life Insurance license.

Again your article is trying to make apples to oranges comparisons and you should consider rewriting it once you gathered some relevant information.

Harry Sit says

Whole life isn’t like anything else. It’s always going to be apples to oranges. If I just want a piece of fruit though, there’s nothing wrong with comparing apples and oranges.

It’s great you brought up the profitable loss ratio. A profitable loss ratio means I pay more for what it takes to insure my unexpected death. It creates a profit to the insurance company. Then they give it back to me as a dividend so I get to see an attractive dividend percentage. Other than a high number I can fool myself with, how does this moving money from my left pocket to my right pocket benefit me exactly?

Steve says

??

Dave says

All life insurance is expensive. The main difference is how those costs are distributed over the life of the policyholder, out to his or her maximum insurable age.

In level term insurance, you calculate the difference between the level premium and 1-year renewable to figure out the implied reserve being built by the insurer. The actual cost of insurance is the 1-yr renewable term. You can see this in whole life by subtracting the interest earnings and cash value out of the policy each year. What you’ll be left with is the net cost for the pure insurance in the policy, which, again, is the same or very similar to the cost for 1-year renewable term.

These costs are not wildly out of proportion to one another, nor should they be.

In whole life, a lot of the costs are paid for up-front. With most term policies, you pay the costs backend, which is why most everyone cancels their term contract after the level premium period… because it’s too expensive. And of course no one buys annual renewable term anymore because it is the pure cost of insurance which, again, is very expensive.

If you did a comparison between whole life and term, keeping the time periods the same (i.e. out to max insurable age), the out of pocket premiums for whole life are always lower than for term because of the time value of money. Cash value in whole life is the reserve that pays for the future death benefit, reducing the net amount at risk (the insurance component of the death benefit). This, in turn, reduces the out of pocket premiums necessary to pay for the insurance.

Of course, no one does that because then the argument switches from “term is cheaper than whole life” to “I don’t need term insurance anymore.”

But, I understand why some people have to make that argument.

You said: “Non-guaranteed is just an estimate. The actual return could be higher or lower. Considering that my friend can buy a 7-year CD at a 3% yield from Andrews Federal Credit Union with government insurance, I don’t see any point in locking in the money longer AND earning less.”

But, do you see any point in potentially earning more? Actual whole life cash value performance over the past 30+ years shows that whole life from the major mutuals beat typical CD rates. Does that mean it will continue? No it does not, but the potential is there and nothing has fundamentally changed how insurers make money and how they operate their insurance business. The only real changes being made now are operating costs are going down as insurers update their legacy systems.

You chose a bad insurer to make the bond argument with since Mass Mutual owns non-insurance businesses, collecting revenue for managing investments, which you forgot to include here. It also obviously profits from its insurance business (wait, isn’t that part of the argument for why whole life is so expensive?). This is why the long-term IRR on cash value exceeds bond returns for some policyholders, particularly those who have held their policies for a long time.

Speaking of a long time, whenever investments are discussed, we talk about time horizons of 30+ years and then conveniently forget to add in the cost of term life insurance to any alt analysis of “BUY TERM and invest the difference,” which drags down return on total outlay. But, whenever whole life enters the discussion, we fully recognize the cost of insurance and start talking about the return on cash value in 10-year time horizons.

Seems legit.

On taxes. Mass explicitly offers an annuity conversion option on its whole life policies, so you can choose to annuitize the policy or take policy loans or take dividend distributions.

You said: “Only those who sell whole life policies tout them.”

Not true, but I see where you’re going with this. The same is true of index funds. Mostly the only people “touting” them are people making money off them, either directly or who are getting endorsement deals or who profit in some other way from investors putting money in them (e.g. HFT who can front run index funds).

But, so what? The only people touting Dyson vacuum cleaners are people selling Dyson vacuum cleaners.

Welcome to capitalism.

Most people who own whole life insurance believe the benefit is so obvious so they don’t have any reason to say anything. They just assume everyone else “gets it.” Every now and then, someone like Peter Neuwirth will come forth and explain why whole life is one of the greatest inventions of the actuarial profession. He doesn’t sell whole life. He is an actuary (retired, I believe), but even when he bought his, he bought it from a life insurance agent and from a company he didn’t work for or consult with.

Rich from the visible policy is happy with his purchase, and he doesn’t believe he was ripped off, in spite of what others have told him. Of course, he’s taken the time to really understand what he has, which is sadly more than what most PF bloggers are willing to do.

Sorry for the rant but it seems like this topic is just not explained correctly, ever.

Harry Sit says

Most everyone cancels their term contract after the level premium period not because it’s too expensive but because they don’t need life insurance anymore. It’s not necessary to keep the time periods out to max insurable age. It’s not an argument. It’s just reality. I just let my term policy expire because no one depends on my income anymore. I’m not even producing a large income anymore for anyone to depend on it. Paying up front for expensive insurance you don’t need toward the end would be a big waste.

Dave says

You said: “Most everyone cancels their term contract after the level premium period not because it’s too expensive but because they don’t need life insurance anymore.”

I understand why you might think that Harry but… let’s be serious.

If that were true, no one would buy new 10 yr level policies after the first level period ended, which people routinely do. And most people would not request conversion options for estate planning and final expense, which they do.

But let’s assume people do lapse their term policies because they no longer need the insurance. Did these people somehow become supersavers during this time period and… if so, where is all their money?

The average 401(k) balance is maybe $100,000-$150,000 out near retirement age. Meanwhile, lapsed term face amounts at that same age are more than double that savings amount. Sometimes they are more than 4 times that amount (particularly for folks who bought 20- yr level policies in their 40s).

Either their advisor oversold them (unlikely) or they failed to achieve the prescribed savings amount by the target year (most studies support this idea).

The real reason people lapse their term policies before they retire is obvious and coincides with what you see in retention/lapse reports — the premiums jump to unaffordable levels (the SOA calls it “premium shock”). It’s not because they’ve replaced the pure insurance with savings or because they suddenly don’t want their term anymore. If that were the case, 401(k) and IRA balances would be much higher than they are.

“It’s not necessary to keep the time periods out to max insurable age.”

Equalizing cash flows or time periods (or both) is absolutely necessary if you’re comparing two things. I don’t think that’s controversial in finance. Otherwise, you have no standard of comparison and don’t come to any sort of meaningful conclusion.

“It’s not an argument. It’s just reality.”

No, it’s a narrative. There’s a difference.

“I just let my term policy expire because no one depends on my income anymore. I’m not even producing a large income anymore for anyone to depend on it. Paying up front for expensive insurance you don’t need toward the end would be a big waste.”

Once again, whole life and term expenses are the same if you are comparing them honestly. If you are comparing 20 years of premiums and expense loading to 55 years of premium and expense loading, then you’re not showing that 55 years of premium is more expensive than 20 years of premium. You’re showing you bailed on the first product and stuck it out and paid more premium in the second, which is not the same as “more expensive.” The out-of-pocket premiums for whole life must actuarially be less than an equivalent term product due to the cash value of whole life.

This is something that’s been explained in every single life and health 101 course offered in the U.S. since at least 1924. That this is still misrepresented on finance sites in 2018 is absolutely fantastic.

As far as strategy goes, I would hope someone with a term policy was able to continually maintain coverage until they replaced their pure insurance, adjusted for inflation. After all, that was the original reason they went with term and not whole life, right? Presumably they have the discipline and money management skills to make it happen. If not, the plan failed.

As a practical matter, most people I know need more money in the future, not less, so perhaps you’re a unique situation in that less money makes more sense than having more money.

Harry Sit says

The opposite of most everyone isn’t no one. Some do realize they need insurance for longer than their original plan. Not everyone. What percentage of policyholders buy a new term policy after the first one ends? Some do request conversion, not everyone. Again, what percentage? I for one am not requesting conversion of my term policy. I don’t think I’m in the minority.

When I buy a term policy when I have a new baby, I need $1 million in case I die tomorrow. When my child grows to 20, I don’t need $1 million anymore but I still have the $1 million policy. If I don’t have $1 million in savings yet I still don’t need it anymore. There’s nothing wrong with letting go a policy with a face amount larger than my savings.

Paying for something you don’t need is always more expensive.

Dave says

I do think you’re in the minority (which is fine). The final expense market is growing, not shrinking. Which means, demand is growing for insurance later on in life.

RE: $1 million in insurance. You buy life insurance in advance of future income and savings, which is discounted to present value. Presumably, you (and by extension, your family) really needs this income or none of this insurance and savings business makes sense. As you say, if you died tomorrow your family would need $1 million, today. Now, either you and your family didn’t really need that $1 million of income or you did. If you didn’t, buying the insurance was a waste. If you did, then you should have saved up the $1 million so you could spend it… because you (and your family) needed it.

William says

I believe many are missing the point regarding what a whole life policy with a company like Mass Mutual actually offers.

Yes, the cash value growth most recently includes ~6% dividend paid annually, and there might be between 15 and 20 years before the max returns show in cash value.

However, the tax free growth, and ability to borrow with cash as collateral rather than removing cash from policy is what makes this a fabulous tool for banking purposes.

You then have nearly instant access to money that you may borrow without removing a dime from your policy, and policy continues to grow.

I have a whole life policy that is inferior to Mass Mutual’s, however, I was able to borrow during a desperate time while I ran into unexpected higher costs that I faced during real estate transactions.

I closed on 3 properties that I thought were move in ready for renters, and was not the case. After putting 20 to 25% down on each property, I was running low on cash.

2 of the properties required repair, and 1 of the 2 require extensive work.

My last resource was my whole life policy that I had been making annual payments on for about 15 years. I borrowed from that policy and paid contractors to complete work on the properties, and within a month had all three properties rented.

The properties remain rented now 5 years later, and I just started paying back the policy loan principal this year.

Yet, because I paid the premium and loan interest yearly, I could borrow more from the policy right now, because cash value has continued to grow.

Now, the 3 properties have all increased substantially in value in just 5 years. I have earned rental income from all 3 properties for 5 years. I was able to get properties while rates were low, and get them rented right away, because I had the Insurance money as a back up.

The cash value of the insurance policy continues to grow.

Now, that is putting your money to work!

Harry Sit says

When you are willing to pay interest, you can always borrow, whether from your life insurance policy or from somewhere else. If you didn’t buy whole life, you would be able to borrow against whatever else you invested in. You don’t pay tax on receiving borrowed money. That’s true for all loans. It’s not unique to whole life policies.

Don says

I’ve heard these comments about whole life many times. “Don’t buy whole life. Just buy term and invest the difference – you’ll get a better return.” On it’s face, this isn’t wrong at all. It’s usually exactly right – theoretically. But I liken this to the similar advice of “Don’t ever pay off your mortgage – you can get higher returns from investing that money instead.”

In reality, how many people will actually invest the difference in cost in these scenarios? The real world rarely works out like these hypothetical situations – unexpected things happen, people have urges to buy things with that extra money, etc… I chose to pay off my mortgage because the peace of mind of doing so was worth much more to me and my quality of life, than the extra couple of percent return I could have gotten on that money the other way.

Similarly, I bought whole life a number of years ago (I had term when I was younger) because it provides certainty in return, and certainty for the folks who will benefit from it when I die. To me (and many others), that certainty is worth more than the extra couple of percent I could theoretically get in return using a combination of other investments and term insurance (which, by the way, there’s no guarantee you’ll be able to get again when your term expires). That certainty also allows me to invest the rest of my money in ways that I likely wouldn’t otherwise have the risk tolerance for. It also allows me to just enjoy life more and stress less.

I get that whole life isn’t right for some (maybe many) – but to say that it’s NEVER right, is really very wrong and misleading. It ignores the fact that, at the end of the day, the whole goal of financial planning is all about quality of life – which, for most people, includes factors other than simply getting an extra couple of percent on some your money.

Meredee says

Well said. That’s exactly what I was thinking.

David says

A few of the previous commenters hit the nail on the head in regards to *practical* benefits of owning permanent life insurance.

But, it’s likely unconvincing to Sit and other critics. There’s an underlying premise in every single one of these anti-whole life posts, both on this site and others, which is fundamentally different from the premise of those who like (and see the benefit of) whole life. That anti-whole life premise (which is really an anti-life insurance premise) is that there is a “need” for life insurance which gradually disappears over time.

There’s a certain appeal to this viewpoint because insurance is expensive, people generally are skeptical of the profit motive of insurers, and people believe their savings strategy is cheap and effective and has virtually no downside.

But insurance is always and everywhere a financing tool which exists to replace that which is lost. The thing being insured is not a necessity, but a value. People buy homeowner’s insurance because they value their home, not because they “need” a $500,000 residence. I’m sure most people could get by living in a studio apartment or some small residence but they don’t want to. Likewise, people buy whole life insurance because they value their future income and savings, not because they (or their family) necessarily “needs” a specific amount of money in the future. Familites without insurance do manage to get by on less money.

In both cases, however, people tend to recognize the significance of the loss and tend to buy insurance to cover the risk of loss. People always need a place to live and likewise they always need income (and savings) until they die. Some people place a higher value on those things than others or recognize insurance as a cost effective way to protect those valuables.

That is what Sit doesn’t “get” or doesn’t agree with. Maybe both.

Harry Sit says

The comments from agents serve as perfect examples of muddying the water with straw man arguments.

It’s a straw man to equate investing with investing in the stock market. You don’t need life insurance to have certainty. You can have certainty from Treasuries and CDs.

It’s a straw man to say you won’t be able to leave money to your family if you don’t buy whole life. If someone wants to pay a lot and leave less to their family, sure, buying whole life does that.

It’s a straw man to say good advice must apply to 100% of the people 100% of the time. There may be a narrow case when it’s better to have whole life. It still makes it a poor fit for 99% of all cases. Of course agents always stoke the fear of missing out. “Maybe you just happen to be that 1% for whom whole life works wonders.” Yeah right.

David says

Hey Harry,

I can understand your position here but I don’t think you’re being very fair.

Forget, for a moment, that it’s life insurance. You’re essentially arguing that a product is unfit for 99% of the population. How can you honestly know this or dictate what other people should value?

Suppose I say “The Toyota Rav 4 is way too expensive for what it is. No one should buy it. Ok, maybe 1% of the population should buy it but all these car salesmen are ripping people off selling this crossovers. Crossovers are dumb to begin with and less efficient than vans. Maybe it makes sense for rich people with lots of money to blow but most people should buy a van.”

Where do I get off telling others what they should buy (thereby insulting a swath of the population whom I don’t know and never met) as well as all car salesmen?

I agree with you there are many different ways to arrange one’s finances. No one needs life insurance, as I stated above. People buy it because they see the value in it. You believe people only buy it because they were tricked into it. You’re wrong but you’re also entitled to your opinion.

You believe people end up with less money by buying whole life but this has been mathematically proven otherwise by folks who design and price these products.

Maybe you think it’s a bad value. That’s fine. Convince as many people as you can. But I don’t think it’s fair to misrepresents the facts or take things out of context. If you can’t see the benefit and disadvantages of something, you’re probably missing something.

Andrew Michaels says

As a CPA it’s painful to read how misguided the author is and he clearly decided to ignore benefits of the aforementioned insurance policy and focus on worse case scenarios. You really did your ‘friend’ a disservice.

Not surprising though since it looks like you sell other/competing financial products.

First of all you cannot compare the policy to an investment unless that other investment is guaranteed not to decrease in value, like these policies are designed. You imply the non-guaranteed portion is a coin toss as to whether it’s paid or not. If you look at almost any of these mutual companies over the last forty years, they’ve paid the non-guaranteed portion like clock work. This isn’t undependable like the stock market.

Did you take into account the tax rate your friend is in? If federal and state tax rates are 30%, that 3% CD you mentioned would actually pay out around 2%. In that case, 4% tax free growth inside a policy for safe money looks good. Not to mention the death benefit.

Regarding the death benefit, I’m always amused with advisors that want to simply disregard the death benefit. I guess the family would give back the $1 -$2 million death benefit if paid out. Also, good luck getting a term policy renewed if a health problem comes up. Guess that’s a risk you’re willing to take.

Did you take into account how the additional income reported on a tax return from your alternatives (CDs, bonds, stocks, etc) can make other items taxable such as social security, or phase out itemized deductions, or bump a taxpayer to higher rates? For retirees, it’s nice to be able to pull cash flow out of a properly structured policy and not report on a tax return, or have the flexibility to not have to sell stocks in a declining market.

You computed a negative return if the money is loaned out. What assinine assumption did you use there…..all of the cash is loaned out the entire time? I’ve never seen anyone advocate that. Pull the money out as a loan to take advantage of opportunities like real estate, or investments. You can have money working in two different places when opportunity arises. Much better than parking it in a commercial bank account. Not to mention there is no underwriting if you want to take a loan, unlike taking loans against other assets you mentioned.

Did you take into account the opportunity costs on the taxes you’ve paid in each year on your investment suggestions (CD, bonds, stocks, etc).

So you’ve basically written an article that ignores the death benefit, federal and state taxes (including future tax rate risk), easy access to cash with no underwriting, uninterrupted compounding interest, etc.

You did your friend a disservice since you didn’t take all factors into account.

Harry Sit says

The litmus test for arguing in favor of a whole life policy is very simple: Do you sell it? If you answer yes, we all know how difficult it is to make someone understand something when his or her income depends on not understanding it.

This post by accident serves as a great honeypot to trap the smoke and mirrors thrown in front of consumers. Revealing your techniques of false arguments will only make the consumers more aware of them.

David says

Except that that’s not really a litmus test at all Harry. A litmus test consists of facts and logic, not motives. A Honda Civic is a great automobile for almost any model year. That salesmen are highly motivated to sell it doesn’t make it a bad automobile. It’s actually irrelevant to whether it’s a great automobile or not, in spite of the fact that their livelihoods depend on selling Hondas.

The test for arguing in favor of a whole life policy is a) whether it is an actuarially sound product and b) whether it solves bonafide financial problems for people and c) whether the market is willing to pay for the protection.

It a big “yes” on all 3 accounts. There is this weird myth that advertising and salesmen can somehow manipulate people into buying things they don’t want. Of course if this were true, we would still be riding in buggies and using whale oil.

Harry Sit says

Honda Civic has independent third parties and current and past drivers saying pros and cons about it. Here we only have financially motivated salespeople saying good things about whole life policies. That tells us something. If you don’t believe a financially motivated salesperson can talk customers into buying something against their best interest, that tells us something still.

Steven Caban says

Harry you are making straw man arguments and talking in circles. Rather than address David’s factual points you are making irrelevant comments about the motivations about anyone with a career in sales.

David says

What makes the Civic good is not the 3rd party reviewers (which often have subtle political and other biases which must exist in order for their organization to survive and sell informational reviews and memberships). What makes the Honda Civic good are Honda engineers.

Once again, motivations of salespeople are mostly irrelevant. We would all be using whale oil and riding horses if salespeople — by and large — were successful in talking people into buying inferior products. The incentive is to sell better products because they tend to pay more and are more profitable. Are there charlatans? Sure there are. They may be a great number of them. But they are not defined by financial motivations. Your obsession with financial incentives is nonsensical and explains nothing and is not rational. Bogle was a salesperson hawking his idea of index funds before they were popular. No one wanted them. No one. And yet they turned out to be beneficial for investors who wanted them. Bogle was clearly financially motivated to sell his idea and funds, else Vanguard would be a non-profit. It’s not. It’s a mutually-owned mutual fund making oodles of money. And Bogle himself was a very wealthy man, arguably more so than your typical life insurance agent.

You’re obsessed by people’s motivations. Motivations you don’t understand because you’re not a psychologist. That you insist on this line of reasoning does reveal something about you and the way you think about these issues.

The reality is whole life insurance is actuarially sound, has been reviewed by 3rd parties (agents, independent actuaries, product development consultants, etc) and also by the FTC (if that matters). There is no credible evidence that these products are bad for consumers. In fact, it’s the opposite, with the caveat that “beneficial” is contextual. But again, the source of whole life’s benefits are not independent actuaries who review it as a product class, but rather the financial engineers (actuaries) who build it. Saying otherwise is, essentially, arguing that professional mathematicians are incompetent at their job. Do you have any evidence of this? Research? Citations?

Andrew Michaels says

Harry, your only response to the points I made is whether I sell it or not? What a weak counterpoint.

I don’t but very familiar with it and implement it myself. I’m a CPA with 18 years in public accounting. I see how inefficient retirement distributions can be with taxpayers in the higher brackets and realize the value of receiving cash flow that you don’t have to report on the tax return at all.

Sorry you’re so jaded about whole life insurance that you either refuse to unbiasedly evaluate or learn about it. Based on your responses and article it’s obvious you have some learning to do on all the factors. Until then, I’d suggest you don’t advise your friends or others on all the pros and cons.

David says

Unfortunately, insurance is above Harry’s pay grade, but on the Internet, everyone can be an expert.

The one legitimate argument you could make against whole life is the longer you hold it the better it looks. Conversely, cashing it in before 10 years is a waste of money. Or, in other words, it takes a long time to pay off. Too long for a lot of folks who are impatient or need all of their money back before then.

But the stuff about commissions, Mass’s investment portfolio, and even some of the surface level stuff about how the policy works is way off the mark. It’s weird too because Mass is one of the more transparent companies when it comes to internal operations. Given Mass’s commission rate on its 10-pay whole life is only 30% of the base premium (the part that’s not the LISR rider), the $6,000 commission assertion is laughable. I think if agents really thought they were getting paid that much, that product would be more popular.

As for the “you’ll only get bond returns” claim, that too is funny because Crandall has publicly talked about this. Mass is one of the few mutuals that doesn’t invest in a more traditional way, employing higher risk strategies on a small amount of their portfolio. They also use leverage to help improve returns on the GIA. One might think this makes Mass a riskier company to do business with, but ALIRT reports show their financials are some of the best in the industry, including surplus, income, and RBC ratios. Harry must have missed that in his thorough analysis of the company’s investment portfolio.

As for the return, let’s dedicate a few CPU cycles to this. The guaranteed return of 2.5% (I’m assuming Harry is correct about this) is 20bp off from a Treasury, but includes a death benefit. So what you’re getting is then equal to a Treasury investment with insurance at a comparative cost of 20bp. Some people are going to think that’s a great deal and some people aren’t and you can’t really tell who is going to want that deal and trying to tell people what they should want is a fool’s errand. You can’t convince a Chevy truck driver to like Ford and you don’t have to because it doesn’t matter. These are not obligatory values people *must* like or dislike.

On the issue of taxes, I’m not sure why Harry thinks investors don’t pay taxes every year. Does he have a hookup at the IRS? Each year investors cash in their investments, they pay taxes on that income. And if the income exceeds a certain threshold, they pay tax on their Social Security, further increasing their tax burden and reducing the net yield they receive from all income sources. That’s why people use insurance. Since Mass continues paying dividends on borrowed amounts, the net cost of a policy loan isn’t dragging down the return the way you illustrate here, Harry.

Again, this is why people use policy loans for income.

Actuaries didn’t create the whole life product to scam consumers or because they’re bad at math. They did it to solve real problems people faced and that the market has, and continues to have.

That SOA study you bloggers love to pass around actually shows this. People keep their large whole life policies for 20 + years. They don’t lapse them, which is why the mutuals have a 95%+ persistency rate. If they had an 80% lapse ratio like some have suggested, there wouldn’t be the surplus available to invest to pay the dividends that Mass has paid for 150+ consecutive years. Sorry Hardy, you’re out of gas.

Andrew Michaels says

Ouch, that was a thorough beat down David. I always wonder why people give their 2 cents when they don’t know a product themselves. Much less write an article about it.

It’d be like me offering my friend advice of how to replace the carburetor in his SUV, even though I have limited knowledge on it. I’d be doing my friend a better service to find someone who knows what they’re talking about.

David says

I can’t speak to Harry’s motivations because I have had only very limited interactions with him. I know at one point he was briefly interested in buying WL.

But it seems he kinda jumped on the bandwagon with the rest of the financial blogosphere. It would be one thing if he had legitimate criticisms, balanced by a sincere understanding of the benefits. But these types of posts are quite thin and perfunctory (and Harry isn’t unique in this aspect), compared to true professionals and product specialists like, for example, Bobby Samuelson, who does have a deep understanding of how these products work, has extensive experience designing them, has an independent review service, and actually consults with insurers on product dev and pricing.

I actually like that folks like Harry exist as advocates for financial literacy. The disadvantage is that they have no expertise in finance and insurance and no unbiased, objective, source to draw on to write these posts.

Brent says

As someone who has one of these types of policies for many years, this article is sadly mistaken.

One of the “solid” pillars that the author of this article uses to build his argument is that the interest charged on the loans taken later in life can be substantial. Unfortunately, for the author’s sake, most of the policies sold to do what this policy is meant to do, provide tax free income, also offer interest free loans after holding the policy for a certain number of years, usually 10-20 years.

Another problem with his arguments in the comments is he keeps coming back to “only people who sell it back it” yet I believe I’m the 3rd policyholder to come into this forum to debunk his article along with a CPA.

David says

MassMutual doesn’t offer interest free loans, but the net cost of the loan is supposed to approach 0% later in retirement due to dividends being paid on policy loans.

I do agree that Harry’s argument that the only people recommending it are the one’s selling it is wrong. It’s embarrassingly wrong and a few minutes of googling this turns up many counterexamples which don’t fit Harry’s narrative, which he conveniently ignores because reasons. There are many CPAs, actuaries, academics, economists, and independent pricing consultants for insurers (none of which sell life insurance) who recommend whole life because it’s an actuarially sound product that does what it says on the box.

This really isn’t that difficult to grasp unless you don’t want to grasp it.

Horton says

I’m an actuary and I would never purchase, nor recommend to a friend or family member, whole life insurance. There’s no need to commingle investing and insurance. Keep it simple – purchase term life (if you need it) and invest the rest (in low cost funds).

David says

For whatever it’s worth, Pete Neuwirth has been an actuary for 35+ years, has a good reputation in the industry, but has a very different opinion. He believes whole life insurance is one of the best inventions the actuarial profession has ever come up with. He writes about it on his blog. I guess there you have it. 2 different opinions from 2 different actuaries. Now what?

andrew michaels says

I think I’ll put more weight into what Pete Neuwirth has to say than an anonymous actuary that wants to “keep it simple”.

As a CPA, I can assure you navigating the tax code and coming up with a strategy to increase retiree’s cash flow isn’t easy. I think whole life, if properly structure and with the right company is beneficial. The IRS loves the “keep it simple” taxpayers though.

Jared says

WOW! Three years of comments. I’ll just say that whether Whole Life is a good product or not, insurance companies sure do make it difficult to determine what the fees/expenses are for their whole life products. It’s nearly impossible to compare across companies the relative insurance cost, expenses, administration fees, etc. Very annoying. I might be fine paying for the extra fees/administration costs because of the tax benefits, but the tax benefits and rates of return are quantifiable so I need to know and be able to compare the fees. And I hate talking to agents. All they want to do is sell.

Jim M says

Upon death doesn’t the life insurance benefit pass on to beneficiary tax free? While, if I leave my 401 k /IRA to my loved one after I die they’ll be required to take my RMD and pay the taxes I deferred? Now I’ve added a tax laibility to my heir and possibly moved them into a higher tax bracket.

Harry Sit says

So does a bank account, a house, and investments outside a 401k or IRA. Passing on to beneficiary tax free is not unique to life insurance. If you take the responsibility and pay the tax you deferred by converting your 401k and IRA to Roth, your heirs won’t have to. So if that’s your concern, do it now.

Jim M says

I agree, before my retirement ROTH’s were not that popular in my day. Now to take an RMD and a Roth conversion would be costly. I did convert some prior to taking my RMD to a Roth. Wish I started sooner.

Ericka Heligman says

What Mass Mutual promised us, we would come to find out was a series of lies that would leave us owing them hundreds of thousands of dollars, instead of them owing us that. I cannot stress how important it is that when you are looking for life insurance, you RUN away from Mass Mutual as fast as you can. My husband and I set up life insurance plans over two decades ago.

During our initial conversations, they showed us what our projected income would be at retirement. In addition, hey showed us what our guaranteed cash surrender value would be and that we would not have to pay premium, because our dividends would cover it (which we have on recording).

Now, I’m 70 and ready to retire and cash out on our policy, but Mass Mutual is coming back to us saying that we owe THEM close to half a million dollars, because we didn’t pay our premium, even though we have it on record that this was them who told us to do it. Moreover, the guaranteed cash surrender value was ¼ of what was promised at the time of sign up. So, now not only have LOST what we thought we had to retire with, but they are saying we need to pay them.

If you are looking for a life insurance plan, look elsewhere. You won’t find out how crooked they are until it’s too late. If you are currently using Mass Mutual, look at your plan NOW, do not wait. Do not let them screw you over the same way that they did us. They are doing nothing to work with us or try to rectify their mistakes. They would not return my calls. It’s absolutely crushing for myself, my husband and for my family. WE are currently reporting them to all state and Federal agencies.