17th-century French mathematician and philosopher Blaise Pascal put forward this reasoning on whether one should believe in God (paraphrasing):

You’re not sure whether God exists. If you believe in God and God doesn’t exist, you live with some unnecessary inconvenience. If you don’t believe in God and God does exist, you receive infinite suffering. The cost of being wrong is much higher in the latter case. Therefore you should believe in God whether God exists or not.

This is called Pascal’s wager. It’s a strategy to minimize loss when you’re not sure.

We face many laws and rules in handling our finances. When we’re not sure how the laws and rules work, we can:

A) Spend hours and hours researching the subject and trying to understand the terminologies and how they fit together. We may still come to the wrong conclusion despite our best efforts.

B) Find and hire an expert and rely on the expert’s opinion. We may not find the true expert and the expert can still be wrong.

C) Use Pascal’s wager and weigh the cost of being wrong. Choose the path of the least costly consequence if we’re wrong.

Sometimes it isn’t worth spending the time or money to find out the true answer to some tricky questions. Using Pascal’s wager is an effective way to minimize the damage in case you’re wrong. Let’s look at some real-life examples I came across lately.

Required to File a Tax Form?

Besides the regular income tax return, there are some obscure tax forms such as the gift tax return, Form 3520 for receiving foreign gifts, and Form 5500-EZ for a solo 401(k) plan. Rules aren’t always clear on when you’re required to file them and when you’re not.

If you’re required to file a tax form but you think you don’t have to file, you’ll face penalties for failing to file as required. If you’re not required to file a tax form but you file one anyway, you waste a small amount of time doing it. Pascal’s wager says you should file a tax form anyway before the deadline.

Filing a tax return whether required or not has other benefits too. Some people had a harder time receiving stimulus payments from the government during the pandemic because they didn’t file a tax return in a previous year when it wasn’t required. It would’ve been much easier if they had filed a tax return anyway.

There’s no tax to pay if you file a gift tax return, a Form 3520, or a Form 5500-EZ before the deadline. Mistakenly thinking you’re not required to file when it’s actually required incurs large penalties. In the case of Form 5500-EZ, the penalty is $250 per day!

When in doubt, file the tax form.

Take the RMD? Based on Whose Age?

The rules on Required Minimum Distributions (RMD) for an inherited IRA are quite complex. It depends on when the original owner died, at what age, whether the IRA had a designated beneficiary, whether the designated beneficiary was a person or a trust, the relationship between the original owner and the beneficiary, the age difference between the original owner and the beneficiary, and so on.

If you’re required to take the RMD from the inherited IRA, the next question is based on whose age. Is it based on the original owner’s age or the beneficiary’s age?

The rules are so complex that Vanguard stopped calculating the RMD for many inherited IRAs for fear of doing it wrong. They punted that responsibility back to the customers and asked them to consult a tax professional.

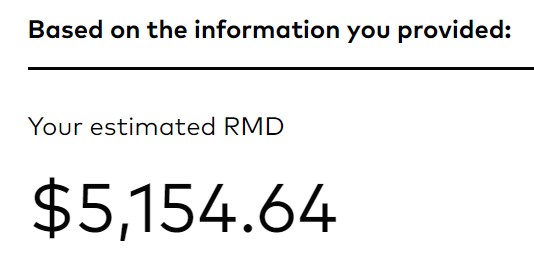

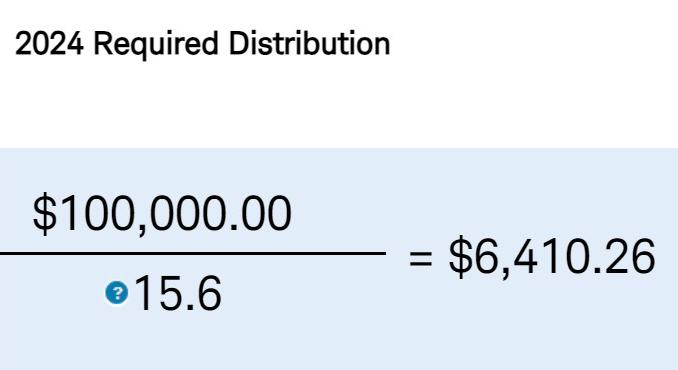

Vanguard still has an online RMD calculator for inherited IRAs. Charles Schwab has one too. The two calculators displayed different results when a reader gave them identical inputs. I tried both of them with this hypothetical case:

- IRA Balance on December 31: $100,000

- Owner’s Date of Birth: May 15, 1955

- Owner’s Date of Death: May 15, 2023

- (Non-Spouse) Beneficiary’s Date of Birth: May 15, 1950

The first result was from Vanguard’s calculator. The second result was from Schwab’s calculator. The results varied by almost 25%! Which one is correct? Of course both calculators have disclaimers to say they shouldn’t be relied on as legal or tax advice.

You can study the complex rules again and again and get a degree in RMDs. Or you can pay a CPA and make sure the CPA really understands this subject and you’re not miscommunicating with the CPA. Or you can see which path gives you the least bad consequence when you’re wrong.

If you take the RMD when you aren’t required to take it, the money comes out of the IRA a little sooner. The money eventually has to come out of the IRA anyway. Timing only makes a small difference. If you don’t take the RMD when you are actually required to take it, you face a much higher penalty.

Similarly, when two calculators give two different RMD amounts and you’re not sure which one is the true minimum, it’s perfectly OK to withdraw a higher amount because the RMD is only a minimum. You’ll be in more trouble if you withdraw less than required. Although I think the Vanguard calculator is correct in the hypothetical case, I would take out the larger amount in case I’m wrong.

When in doubt, take the RMD. When in doubt, withdraw a larger amount.

The Last Day to Buy I Bonds

I Bonds credit interest by the month. It doesn’t matter which exact day in the month you buy I Bonds. You get interest for the entire month as long as you hold I Bonds on the last day of that month. Therefore it’s better to buy I Bonds close to the end of a month.

How close though? When is the last day to buy I Bonds and still get the interest for that month? Is it the last business day of the month? Or is it the second last business day of the month? Or the third last business day of the month?

If you think it’s the last business day of the month but the deadline is actually the second last business day of the month or if you think the deadline is the second last business day of the month but it’s actually the third last business day of the month, your purchase will miss a full month’s worth of interest. If you think the deadline is sooner but it’s actually later, you’re buying a little too soon and you forego earning interest in your savings account or money market fund for a day or two. Not earning interest for a day or two is a lot better than missing a full month’s worth of interest.

I give it a week when I buy I Bonds. The same goes for paying taxes. I set the date of my payment to a week before the due date. If anything goes wrong I still have time to fix it and try again.

When in doubt, do it sooner.

Solo 401k Contribution Limit

I have a Solo 401k contribution limit calculator for part-time self-employment. A reader asked me about it because his Third-Party Administrator (TPA) gave him a lower contribution limit. Although I’m confident that my calculator is correct, I said he should go with the lower amount from the TPA.

The calculated contribution limit is only a maximum. No one says you must contribute the maximum. It’s perfectly OK to contribute less than the maximum. If the TPA knows something that I don’t, it’ll be a mess if the reader goes with the higher amount from my calculator and exceeds the legal maximum.

When in doubt, contribute less.

***

You may still be wrong after spending the time and/or money to find the true answers to some tricky questions. You might as well make it easy by evaluating the consequences when you’re wrong. If the consequences are lopsided between two choices, as they often are, use Pascal’s wager and choose the path that costs less when you’re wrong.

Learn the Nuts and Bolts

I put everything I use to manage my money in a book. My Financial Toolbox guides you to a clear course of action.

Susan says

Thanks Harry. These articles on how to make decisions are so helpful. It is often these psychological roadblocks that stop us from making sound financial decisions.

Would you consider tackling a topic that goes something like: how to prioritize changes in our finances? I am revisiting our finances after many years of “set it and forget it”. But I know more now, after attending the Bogleheads conference. But which changes to make first? Which ones make the biggest improvement financially? For instance, now I know to put bonds in a tax sheltered account. And we need to do rollovers for a lot of little Roth IRAs from old employers. And the assset balance isn’t quite right anymore. And now there are new tools that will automatically re-balance. These are all financial tasks that will take some time to tackle. And to be honest, I might lose steam before getting to them all.

Thanks for all your thoughtful articles!

DS in GA says

Your to-do list doesn’t seem daunting at all. I bet you can do it.

Are you being forced to do the rollovers, or is it more a desire for simplification? If your Roth amounts are in 401Ks and there is no mandate to move them out, maybe you don’t. You get creditor and bankruptcy protection in 401K accounts you don’t have with IRAs. However, if you must do the rollovers, I’d concentrate on the mandated ones first and then get to the rest when time allows. You’ll likely find once you do the first one, the process isn’t all that difficult anyway and maybe just do them all in a weekend morning.

There’s a psychology for how individual people are motivated to tackle financial tasks. Take debt repayment. Logically, you might focus on paying down the highest interest rate debt first. That’s what I did when I had some debt early in my career. However, some people need to see progress more swiftly and they may benefit (by sticking with the repayment tasks vs giving up due to not seeing material downward movement of the principal) by paying off the smallest debt amount first, then the next smallest, etc. Seeing their list of debts get smaller is a better approach for them due to how they perceive their progress.

For your asset allocation task, is it really out of whack? If not, I wouldn’t stress over it too much. Personally I think AA is over-complicated for most people. A nationally known and respected advisor I know has 100% of her own retirement accounts in stock mutual funds. Not a bond in sight. That’s anathema for the 60:40 set but I agree with her approach (until you’re approaching retirement age) because she has a couple of decades until retirement and she can handle the purported greater standard deviations of her returns in exchange for expected larger returns. I personally use fixed income only for my current deferred comp payments that we’re living on for the next 12-13 years (55:45 ratio stock mutual funds to 5% money market). I have another bucket that is 100% in stocks and stock mutual funds that I use for things like paying for weddings, more extravagant vacations, and other sporadic 1-offs. Lastly, I have a long-term retirement bucket that I won’t need for another 12-13 years (ie, post deferred comp) that is 100% invested in stock mutual funds. I also don’t have a penny invested in overseas funds. Over the decades I haven’t seen the value of investing in generally lower returns given I can accept the swings in the US market. My point here is that asset allocation is important to your investing but it doesn’t have to be as complicated as many models (and CFP courses) advise. When I see large cap, mid cap, and small cap funds in a recommendation, for both growth and value funds (so 6 funds for this alone), and then international funds, bonds, intl bonds, TIPS, REITS, and even gold all included in a bid for diversification I just ignore and focus on simple yet generally effective. I chase average returns not outsized gains and if the average investor wants to they can get them from as little as a total US stock market index fund, a total international (ex-US) index fund, and a total US bond market fund. You could split the bond $ into an intl bond fund as well, and call it a day. I just use the S&P 500 myself but total stock market is good, too.

Lastly, I’m guessing Harry has already tackled your topic. You may try a search and see. Good luck.

Cynthia says

Your articles are the best out there, but this one is even more amazing than usual. Thank you, and please keep doing what you’re doing. We all need you!

Craig says

You have to strike the right balance with this approach though. For example, you could have decided that doing the backdoor Roth is too risky, and miss out on getting tens of thousands of dollars into a tax-free account over the years, until Congress eventually said it’s fine. Or you could pass on tax-loss harvesting, or miss out on market gains by staying in cash for 30 days after selling for fear of the “substantially identical” wash sale rule.

Susan says

This is a very helpful article! I often work so hard to figure things out but I think, as your article suggests, a better way to do things is to think of the consequences and then do the appropriate thing. Plus it makes life easier. I’ve also learned a little philosophy today.

Thank you for your articles. I don’t usually post a comment, but I do get a lot out of your writing.

Mapleton Reader says

One area that I would appreciate you writing about, is planning for the expiration of the 2018 TCJA (if not renewed). While there are many moving parts in this, it seems like it would be useful to do more (or larger) Roth Conversions to reduce future RMDs and possibly higher taxes (with only a smaller downside if the TCJA was extended as your article suggests).