The previous post Buying CD in a Brokerage Account vs Bank CD or Treasury talked about the advantages and disadvantages of buying brokered CDs versus buying CDs directly from a bank or a credit union or buying Treasuries. It ended with these steps when you’re considering buying brokered CDs:

1. Decide what term you want because selling brokered CDs before maturity will be costly.

2. Check DepositAccounts.com for the best rate on a direct CD for your term. Weigh the convenience of brokered CDs against giving up yield and the early withdrawal option.

3. Check the yield on Treasuries for your term. Adjust it for the state and local tax exemption if you’re buying in a regular taxable account.

4. Only compare non-callable brokered CDs with direct CDs and Treasuries. Demand a large yield difference if you don’t mind callable CDs.

Now we go into the logistics of how to buy a CD in a Fidelity or Vanguard brokerage account with a real-life example.

Suppose we want a 3-year CD because we’re comfortable committing to holding it for three years.

Research Direct CDs

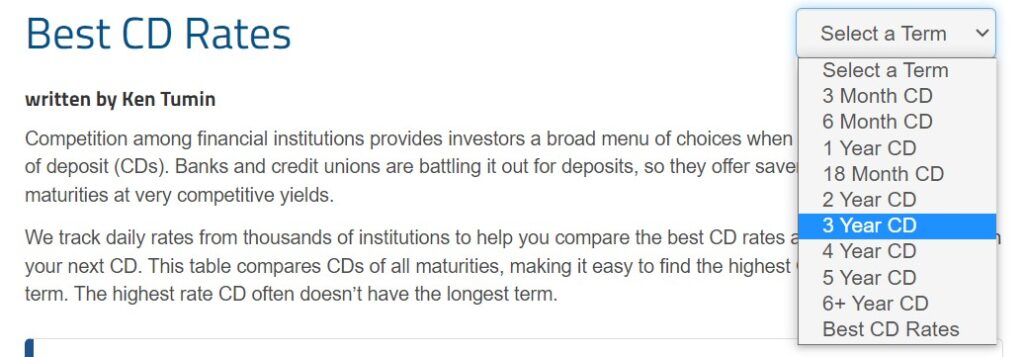

We go to DepositAccounts.com to see the current best rates offered directly by a bank or a credit union. We want the yield on a brokered CD not to be too far off. We select the 3-year term in the term dropdown.

We see that the highest rate is 5.65%. However, several CDs at the top of the list are variable-rate CDs, which means the rate can drop during the term. We don’t want that.

We go down the list to find a CD with a fixed rate. We see that the best 3-year fixed-rate CD pays 5.13%. It requires opening a new account at a credit union though. We like the convenience of using our existing brokerage account without having to open another account but we don’t want to give up too much on the yield.

Research Treasuries

We also check Treasuries. This bond yields page from Fidelity doesn’t require a login.

We see the 3-year Treasury yield is 4.36% right now. Because Treasuries are exempt from state and local taxes and we’re buying in a regular taxable account, we calculate the Treasury’s tax-equivalent yield using this formula:

treasury yield * ( 1 – federal tax rate ) / ( 1 – federal tax rate – state tax rate )

It comes out to 4.36% * ( 1 – .22 ) / ( 1 – .22 – .06 ) = 4.72% when our federal tax rate is 22% and our state tax rate is 6%. A CD that’s fully taxable for both federal and state must have a yield this high to beat the Treasury. We don’t have to make this adjustment if we’re buying in an IRA or if we live in a no-tax state.

Now we want to see if we can beat the 3-year Treasury if we buy a brokered CD and how close we can get to the best rate from a direct CD.

There are two ways to buy a brokered CD: new issue and secondary market. Whether you’re looking for new issues or the secondary market, it’s best to look when the market is open (9:30 – 4:00 Eastern Time). You’ll see more choices during those hours.

New Issue

Buying a new-issue brokered CD means buying a brand-new CD offered by a bank through the broker. You see the rate and the terms of the CD set by the bank. You pay the face value to get the CD if you like the rate and the terms. The broker doesn’t charge you a fee because they’re getting paid by the bank to sell it.

Secondary CDs

Buying on the secondary market means buying from a dealer who bought the CD from a previous owner. The price the dealer asks for may be above or below the face value of the CD depending on the existing rate of the CD relative to the current market rate. The interest payments and the principal repayment from the bank are still based on the face value and the original rate because the bank doesn’t care whether you’re the first owner or the second or the third owner. The CD still has FDIC insurance.

The broker charges you a commission to buy CDs on the secondary market. The commission is typically $1 per $1,000 in face value. Paying a commission reduces the yield you get from the CD.

You also must pay accrued interest to the dealer. If the CD pays interest every six months and it’s been two months since the last interest payment date, you owe two months’ worth of interest to the dealer. You’ll still receive six months’ worth of interest from the bank when the CD pays interest next time, which reimburses you for the accrued interest you paid to the dealer.

If the price of the CD is above 100 because the coupon rate of the CD is higher than the quoted yield, you’re paying more than the face value of the CD. The difference above the face value isn’t insured by the FDIC. Avoid this type of CD or, if you must, only choose one from a bank that’s too big to fail.

If you’re buying in a regular taxable brokerage account, paying a price above or below the face value with the trading commission and accrued interest complicates your taxes. If you prefer to avoid this complication, stick with new-issue brokered CDs when you’re buying in a regular taxable brokerage account. The tax complication doesn’t apply when you’re buying in an IRA.

Fidelity

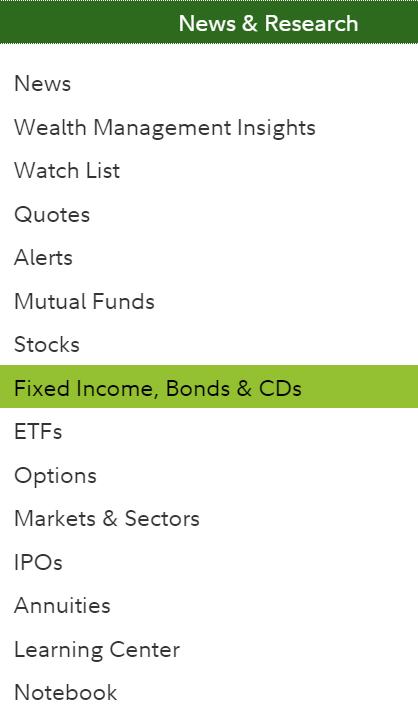

If you use Fidelity, click on “News & Research” and then “Fixed Income, Bonds & CDs” after you log in to your Fidelity account. If you use Vanguard, please jump ahead to the next section for Vanguard.

You get to the same bond yields page.

New Issues

Clicking on the link under the term we want gives us this list of new issue CDs being offered:

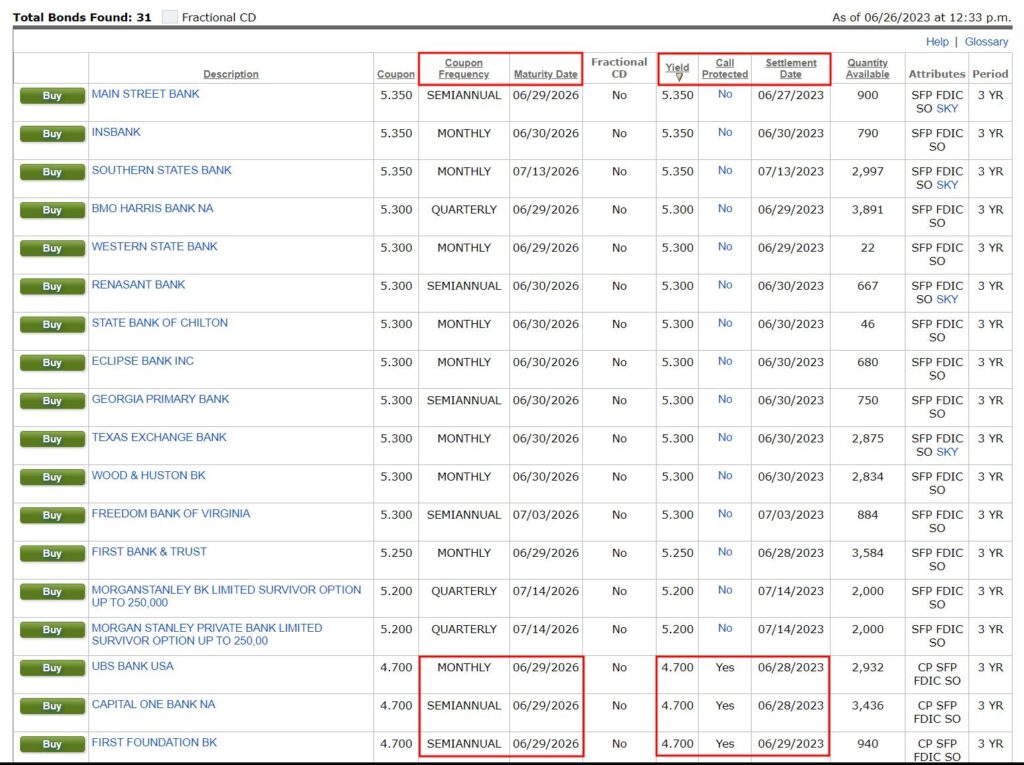

“No” in the “Call Protected” column means the CD is callable (not protected from a call). In general, we want to avoid callable CDs because although the advertised rate is higher, we’re not locked in to earn it for the full term. We see in this list that the highest yield on a non-callable (Call Protected = Yes) 3-year CD is 4.7%.

“Coupon Frequency” shows how often the CD pays interest. Some CDs pay monthly, some pay quarterly, some pay semi-annually, and some short-term CDs pay at maturity. Which way is better is only personal preference. We prefer less frequent payments so that we don’t have to deal with the received cash. Some others may prefer to receive cash more frequently to meet cash flow needs.

“Maturity Date” is when we’ll get our principal back. “Settlement Date” is when the broker will debit our cash to buy the CD. Our cash earns interest in the money market fund until the settlement date.

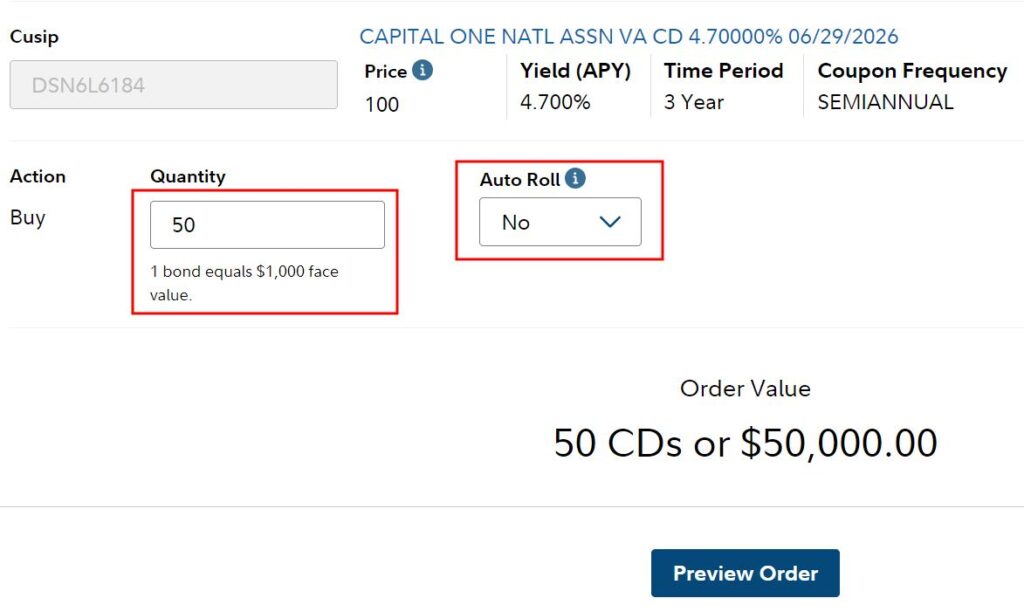

Suppose we want to buy that CD from Capital One. We see this page after we click on “Buy.”

We must buy in $1,000 increments. We enter 50 under “Quantity” if we want to buy $50,000 in face value. Fidelity offers an optional “Auto Roll” feature. If we choose to use it, Fidelity will automatically buy another brokered CD of the same term when this CD matures. We choose not to use the Auto Roll feature because we’d like to evaluate whether a brokered CD is still competitive with a Treasury note at that time. We can set a reminder in Google Calendar to reinvest when our CD matures.

If we’re buying in an IRA or if we live in a no-tax state, the 4.7% rate on a non-callable CD is still higher than the 4.3% rate on a 3-year Treasury. We can decide whether the 0.4% extra yield is worth the poor liquidity in a brokered CD. However, when we’re buying in a regular taxable account, the 4.7% rate on a non-callable CD isn’t any better than the tax-equivalent yield of a 3-year Treasury after we adjust for the state and local tax exemption from the Treasury. We might as well just buy a Treasury note.

Secondary CDs

Before we abandon the idea of buying a brokered CD in favor of buying a Treasury note, we’re curious whether we can do better by buying a brokered CD on the secondary market.

We go back to the bond yields page by clicking on “News & Research” and then “Fixed Income, Bonds & CDs.”

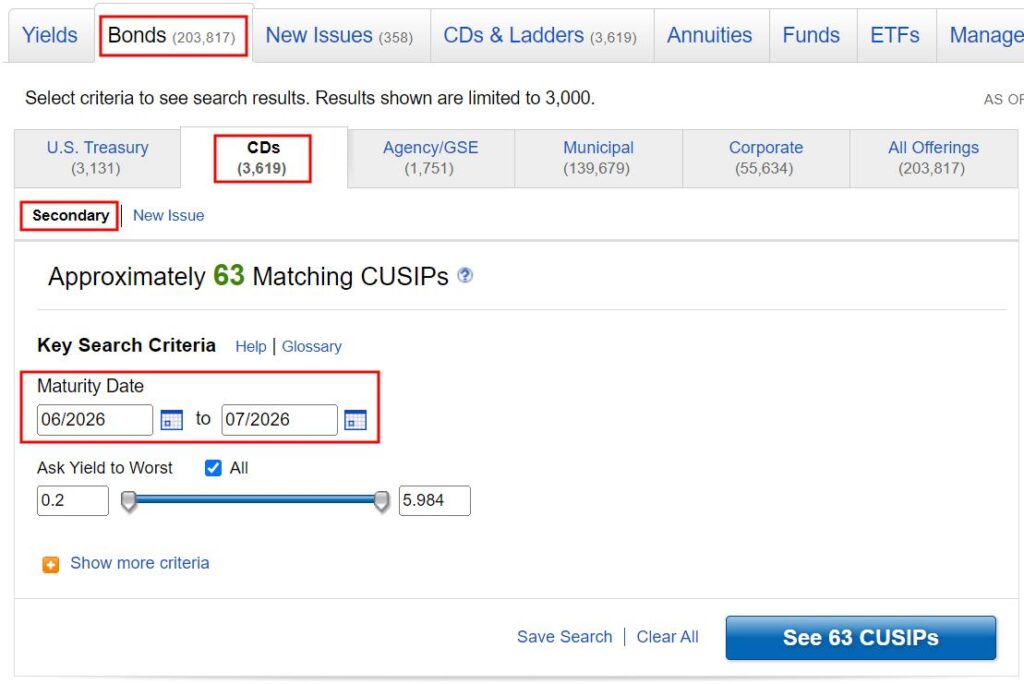

Click on the “Bonds” tab and then the “CDs” sub-tab. We’re now searching for CDs on the secondary market. Enter a date range for the maturity date and then click on “See xx CUSIPs.”

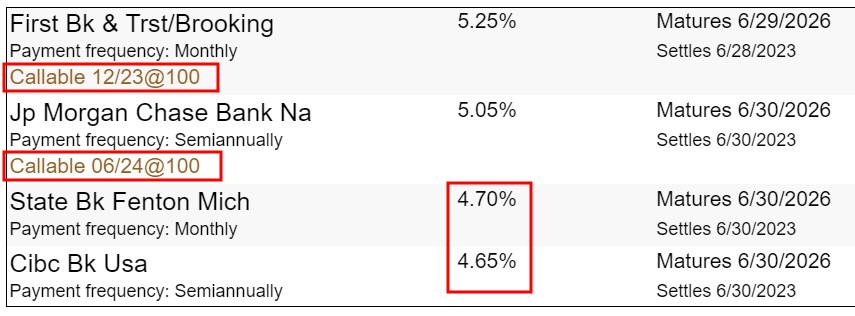

First, click on “Yield to Worst” in the “Ask” columns to sort the list by the offered yield.

When we see a date in the “Next Call Date” column, that CD is callable. As we still want to avoid callable CDs, we see the highest yield for a non-callable CD is 4.751%.

The “Price Qty(Min)” column gives us three numbers. The first number is the price. It’s expressed as a percentage of the face value. 99.585 means $995.85 per $1,000 face value. We’ll have full FDIC insurance when the price is below 100. The second number shows how much in face value is available to buy. 8 means $8,000 in face value is available in that one. The third number in parenthesis shows the minimum purchase. 1 means a minimum of $1,000 in face value. The CD in the next row at a yield of 4.750% has $95,000 in face value available but we must buy at least $20,000 in face value.

Because we must pay a commission when we buy a secondary CD, our net yield will be lower than the gross yield we see in the table. This makes it not worth the hassle to buy a secondary CD when the 4.75% rate isn’t much higher than the 4.7% rate on a new issue CD to begin with.

In summary, our round of research shows:

| 3-year CD directly from a credit union | 5.13% |

| 3-year Treasury | 4.7% (tax-equivalent), 4.3% in IRA |

| 3-year new issue non-callable brokered CD | 4.7% |

| 3-year secondary non-callable brokered CD | 4.7% |

Given these rates, if we prefer the convenience of keeping everything in the brokerage account, we’ll buy a 3-year Treasury note (see How To Buy Treasury Bills & Notes Without Fee at Online Brokers and How to Buy Treasury Bills & Notes On the Secondary Market). We’ll buy a CD directly from a credit union for a higher yield if we don’t mind opening a new account there. If we’re buying in an IRA, we’ll consider a new issue brokered CD but we have to weigh it against the poor liquidity. Buying a brokered CD on the secondary market doesn’t give us a meaningful bargain at the moment we looked.

Brokered CDs are just another tool. They don’t always work better than Treasuries and direct CDs. The tradeoffs will change as rates change. Sometimes brokered CDs are more competitive and sometimes they’re less competitive. Sometimes you find a bargain in a secondary CD and sometimes you don’t. The research process I’m showing in this example will stay the same.

Vanguard

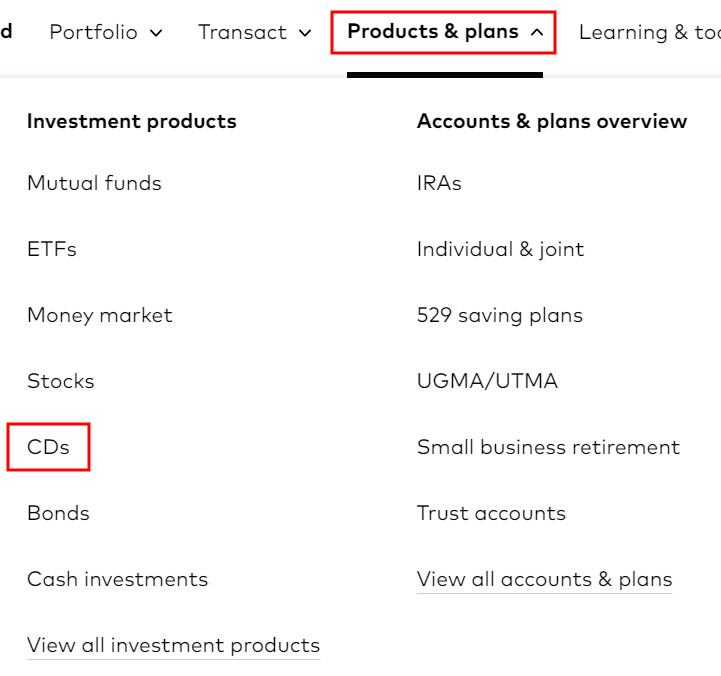

It works similarly in a Vanguard brokerage account. Click on “Products & plans” and then “CDs” after you log in to your Vanguard account.

New Issues

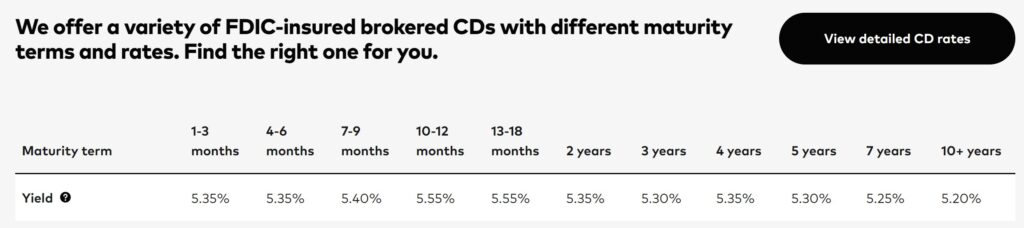

Scroll down a little and click on the big “View detailed CD rates” button.

The next page displays an old-style page in a frame. If you’re using the Safari browser on a Mac and you don’t see anything, turn off “Prevent cross-site tracking” in your Safari settings.

Find the term you’re interested in and click on the rate. The displayed rate may be from a callable CD.

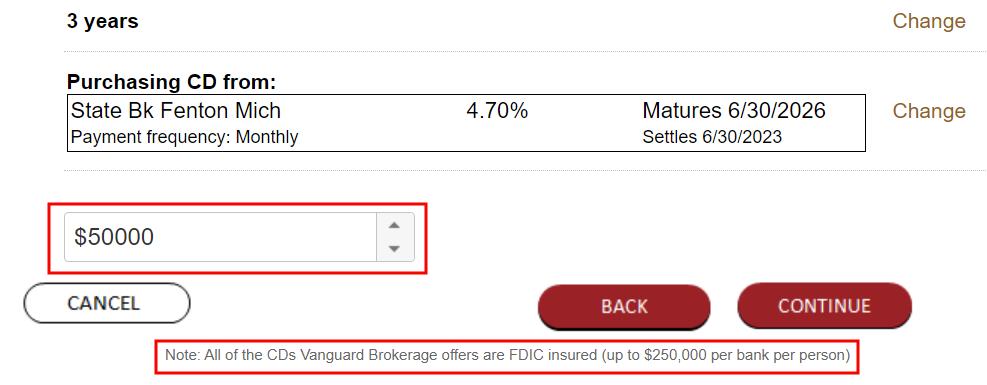

We keep scrolling down to find the first non-callable CD. It pays 4.7%. This is the same rate we see in Fidelity but it’s from a different bank. Suppose we want to buy $50,000 in this CD. We click on that row and then the “Continue” button. We see this order page:

It doesn’t matter that the CD is from a bank we haven’t heard of because it has FDIC insurance. We also must buy in $1,000 increments. We enter 50,000 in the quantity box. Vanguard doesn’t offer an “Auto Roll” feature. We can set a reminder in Google Calendar to reinvest when our CD matures.

Secondary CDs

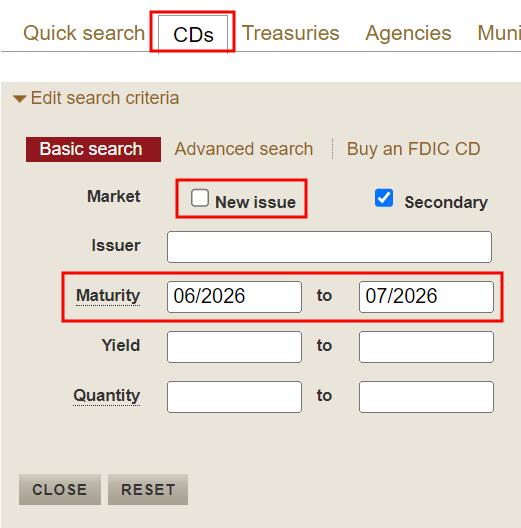

We’re also curious whether we can find a better bargain on the secondary market. Click on “Cancel” to go back to the previous page.

Click on the “CDs” tab. Uncheck the box for “New issue” and check the box for “Secondary” because we’re looking for secondary CDs. Enter a date range for the maturity date and click on “Search.”

We look carefully to skip the callable CDs. The second row in the “Yield to worst” column shows the yield when we buy. The search results show that the highest yield available in a non-callable CD on the secondary market is 4.772%. The second row in the “Price” column shows the price we must pay. We want to see a number below 100 to get full FDIC insurance. The second row in the “Qty” and “Min. qty” columns shows how much is available and the minimum purchase amount. 48 under “Qty” means $48,000 in face value is available and 25 under “Min. qty” means we must buy at least $25,000 in face value.

If we want to buy $50,000 worth of CDs, that CD from Cross River Bank only has $48,000 available. We’ll have to mix and match or go down to the next one from Discover Bank for a slightly lower yield at 4.754%. Either 4.772% or 4.754% still has to be reduced by the trading commission we must pay for buying secondary CDs. The net yield after the commission isn’t meaningfully higher than the yield on a non-callable new issue CD.

We come to the same conclusion using Vanguard as we did using Fidelity:

| 3-year CD directly from a credit union | 5.13% |

| 3-year Treasury | 4.7% (tax-equivalent), 4.3% in IRA |

| 3-year new issue non-callable brokered CD | 4.7% |

| 3-year secondary non-callable brokered CD | 4.7% |

Given these rates, if we prefer the convenience of keeping everything in the brokerage account, we’ll buy a 3-year Treasury note (see How To Buy Treasury Bills & Notes Without Fee at Online Brokers and How to Buy Treasury Bills & Notes On the Secondary Market). We’ll buy a CD directly from a credit union for a slightly higher yield if we don’t mind opening a new account there. If we’re buying in an IRA, we’ll consider a new issue brokered CD but we have to weigh it against the poor liquidity. Buying a brokered CD on the secondary market doesn’t give us a meaningful bargain at the moment we looked.

Brokered CDs are just another tool. They don’t always work better than Treasuries and direct CDs. The tradeoffs will change as rates change. Sometimes brokered CDs are more competitive and sometimes they’re less competitive. Sometimes you find a bargain in a secondary CD and sometimes you don’t. The research process I’m showing in this example will stay the same.

Learn the Nuts and Bolts

I put everything I use to manage my money in a book. My Financial Toolbox guides you to a clear course of action.

Barbara says

I appreciate the timeliness of this post as we recently transferred our IRAs to Fidelity. Your detailed steps regarding the process on Fidelity’s website is very helpful as we are just learning our way around the site. We plan to put part of our funds in CD ladders as we want to start making annual Roth conversions so as each ladder matures, we can convert those funds.

I was wondering what you thought about buying VTSAX through our Fidelity account. I assume there would be a fee? We are very new to investing and are not sure about leaving much cash in the money market cash clearing account. I saw that it has a fairly high expense ratio, so my thought is to put a chunk into short-term CDs to reduce the expense. Also any other helpful tips about investing through Fidelity would be appreciated.

Harry Sit says

Fidelity charges $75 to buy VTSAX but no fee to sell, hold existing shares, or automatically reinvest dividends. You can buy VTI, which is the ETF version of that same fund, without a fee.

As noted in this post, Treasury Bills are an alternative to short-term CDs. Rates are comparable when you’re buying in an IRA but Treasury Bills are much more liquid in case you need to sell them before maturity.

Jeff says

“We choose not to use the “Auto Roll” feature because Fidelity can pick a callable CD for the auto roll and we don’t like callable CDs. ”

For auto-roll on a CD-ladder at Fidelity, it has not worked this way for me–it will only put non-callable CDs in the initial ladder and will choose the highest yield non-callable CD when rolling. Does the auto-roll work differently for non-ladder auto-rolls, or is there possibly a setting to control it?

Harry Sit says

You’re right. Fidelity says callable CDs aren’t eligible for auto roll. I edited it to say “We choose not to use the Auto Roll feature because we’d like to evaluate whether a brokered CD is still competitive with a Treasury note at that time.”

The difference in auto roll for a single CD versus a ladder is that they will choose a CD with the same interest payment frequency when they roll a single CD whereas the interest payment frequency can change when they roll in a ladder.