Buying CDs in a brokerage account doesn’t require opening a separate account with a bank. Is it worth it?

What Is a Brokered CD

When you see CDs offered in your Fidelity, Vanguard, or Charles Schwab account, they’re brokered CDs. A brokered CD is issued by a bank and sold through brokers.

The CD has FDIC insurance. If you have other money at the same bank that issues the CD, your FDIC insurance limit is aggregated across your direct holdings and your brokered CDs from that bank.

A brokered CD is safe as long as you stay under the FDIC insurance limit. I bought a brokered CD from a bank in Puerto Rico during the 2008 financial crisis. FDIC paid me in full with interest when that bank failed. I didn’t have to file any claim. The cash just showed up in my account about a week after the announced bank failure.

How a Brokered CD Works

Except for having FDIC insurance, a brokered CD works more like a bond.

1 CD is $1,000 of principal. You buy them in $1,000 increments. Fidelity offers “fractional CD” at $100 increments on some CDs. Brokers typically don’t charge fees for buying brokered CDs or holding them in your account. You will see fluctuating prices for the CD after you buy it in your brokerage account but you’ll be paid the full face value when it matures.

Brokered CDs don’t compound. Interest payments from the CD are paid into your brokerage accounts as cash. The payment frequency varies depending on the CD. It can be monthly, quarterly, or semi-annually. Some short-term CDs only pay interest at maturity. If the interest rate on a brokered CD is 5% and it pays semi-annually, you’ll receive $25 in interest per $1,000 of principal every six months.

You get the principal back as cash when the CD matures. If you want to get out of the CD before it matures, you must sell it on the secondary market to another buyer.

Brokered CD vs Direct CD

Brokered CDs have some advantages over CDs you buy directly at a bank or a credit union. They also have two large disadvantages.

Everything In One Account

It’s more convenient to buy brokered CDs from several different banks in one brokerage account than to open a separate account at each bank. This is helpful especially when you buy short-term CDs, but if you’re considering a 5-year CD, you only open an account once when you buy directly from a bank or a credit union and you’re good for five years.

Competitive Rates

Because banks know that brokers present brokered CDs in a table sorted by the yield, they have to offer a competitive yield to show up on top. They can’t prey on customers not being up to speed on the going rates. Many banks still offer very low rates on their websites but they have competitive rates on brokered CDs.

Not all banks offer brokered CDs though. Some banks, and especially credit unions, offer CD specials only to their direct customers. You should check the best rates on DepositAccounts.com to see whether a bank or a credit union offers a better rate than the rate you see from a brokered CD.

No Renewal Trap

By default, a brokered CD is automatically cashed out when it matures. Some brokers offer an “auto roll” feature to buy another brokered CD of the same term when one CD matures but you specifically sign up for that feature only if you want it.

Most banks and credit unions automatically renew a matured CD. The new CD they renew you into often has a low rate. You’ll have to tell them to stop the renewal within a short window. If you aren’t on top of it, you’ll either be stuck with a low rate or you’ll have to pay a big early withdrawal penalty that can eat into your principal. See Beware: Banks Auto-Renew CDs with a Short Window to Back Out.

Call Risk

Many brokered CDs are callable, which means the bank has the right to terminate (“call”) the CD before the stated maturity date.

Having your CD terminated prematurely is the opposite of you refinancing your mortgage when the market rate goes down. The bank has the choice to terminate the CD or not. You have no right to refuse.

Some callable CDs have preset dates when the bank may exercise its right to terminate. Some are continuously callable, which means the bank has the right to terminate at any time after a certain date.

Naturally, the bank will only terminate the CD when the going rate goes down. You were counting on earning the guaranteed interest for the full term. All of a sudden the bank decides to pay you out early. You get your money back but you can only earn less now because the going rate is lower. On the other hand, if the going rate goes up, the bank chooses not to terminate the CD, and you’re stuck with a below-market rate until maturity.

A callable CD gives you the worst of both worlds. Most direct CDs aren’t callable. You’re guaranteed to enjoy the rate you locked in for the full term when you buy a CD directly from a bank or a credit union. You should compare only non-callable brokered CDs with direct CDs or demand a substantially higher yield from a callable brokered CD.

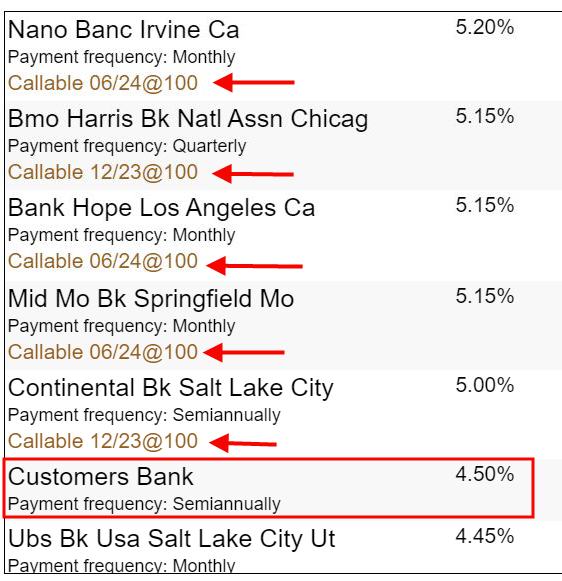

For example, as I’m writing this, Vanguard shows the best 5-year brokered CD pays 5.2% and DepositAccounts.com shows the best 5-year direct CD from a credit union pays 4.68%. That makes brokerage CDs look attractive until you find out that the brokered CDs with higher rates are all callable.

The best rate on a 5-year non-callable brokered CD is only 4.5%. This is lower than the 4.68% yield on a 5-year CD you can get from a credit union. You will have to weigh the convenience of buying a brokered CD against getting a lower yield or taking the call risk.

Can’t Withdraw Early

A CD bought directly from a bank or a credit union has a big advantage over a brokered CD because you can break it by paying a preset early withdrawal penalty. Some direct CDs have no early withdrawal penalty (“no-penalty CDs”).

A brokered CD doesn’t offer an option to withdraw early. You must sell the brokered CD on the secondary market to a bond dealer if you want to get out early.

There may not be a dealer interested in your CD when you want to sell. If there’s a dealer, the price you receive from selling the CD is determined by the current market rate at that time minus a large haircut. It may be much lower than paying the preset early withdrawal penalty on a direct CD.

Breaking a CD isn’t only for an unexpected need for cash. When interest rates go up sharply, it makes sense to pay an early withdrawal penalty and reinvest at a higher yield. I broke all my direct CDs last year by paying the early withdrawal penalty because the CD Early Withdrawal Penalty Calculator shows that I will end up with a higher value than holding the CDs to maturity. I wouldn’t have had this option had I bought brokered CDs.

Reinvestment Risk

When you have a CD directly from a bank or a credit union, you have the option to have the interest paid out to you or to reinvest the interest in the CD. If the going rate goes up, you choose to have the interest paid out and earn a higher yield elsewhere. If the going rate falls, you choose to reinvest the interest at the original higher yield.

You don’t have this option with a brokered CD. All interest is paid out in cash. If the going rate goes down, you can only earn a lower yield on the interest.

Brokered CD vs Treasury

Suppose you like the convenience of brokered CDs and you don’t mind giving up a small difference in yield and the option to withdraw early. Still don’t pull the trigger just yet. You always have the option to buy Treasuries instead.

Brokers sell brokered CDs because they’re paid by the banks to sell the CDs. You see more advertising from the broker for brokered CDs than for Treasuries but you may be better off buying Treasuries anyway.

Because Treasuries have a direct guarantee from the government versus through a separate government agency (the FDIC), brokered CDs must overcome several hurdles before you consider them. Otherwise you just buy Treasuries.

Yield May Be Lower

Brokered CDs don’t always pay more than Treasuries of a comparable term. For example, as I’m writing this, the best six-month brokered CD pays 5.3% APY whereas a six-month Treasury pays 5.4%.

Don’t buy a brokered CD only because the rate sounds attractive on the surface. Always find out first what a Treasury is paying for the same term. See How To Buy Treasury Bills & Notes Without Fee at Online Brokers and How to Buy Treasury Bills & Notes On the Secondary Market. Don’t bother with a brokered CD when a Treasury pays more.

No State Tax Exemption

If you buy in a regular taxable brokerage account, interest from Treasuries is exempt from state and local taxes. Interest from brokered CDs is fully taxable by the state and local governments. Brokered CDs must pay more than Treasuries after adjusting for this state and local tax exemption.

If you take the standard deduction or if you itemize deductions but your state and local taxes are already capped by the $10,000 limit, you don’t get any federal tax deduction for paying additional state and local taxes. When your federal marginal tax rate is f and your state and local marginal tax rate is s, the tax-equivalent yield of a Treasury with a quoted yield of t is:

t * ( 1 – f ) / ( 1 – f – s )

For example, as I’m writing this, the best 1-year brokered CD has a yield of 5.4% and a one-year Treasury has a yield of 5.24%. When your federal marginal tax rate is 22% and your state and local marginal tax rate is 6%, the tax-equivalent yield of the Treasury is:

5.24% * ( 1 – .22 ) / ( 1 – .22 – .06 ) = 5.68%

That means a CD must have a yield of 5.68% to earn the same amount after all taxes as a Treasury with a yield of 5.24%. Although the brokered CD with a yield of 5.4% appears to pay more than the Treasury with a yield of 5.24% at first glance, it actually pays less than the Treasury after you take all taxes into account.

If you itemize deductions and your state and local taxes aren’t already capped by the $10,000 limit, you still get a federal tax deduction for the state and local taxes you pay on the interest from the CD. The tax-equivalent yield formula is:

t / ( 1 – s )

In that case, the CD still needs to yield 5.24% / ( 1 – .06 ) = 5.57% to beat the Treasury.

You don’t have to make a tax-equivalent yield adjustment if you’re buying in an IRA or if you don’t have state and local taxes.

Treasuries Aren’t Callable

Many brokered CDs are callable whereas all Treasuries aren’t callable. You should compare only non-callable brokered CDs with Treasuries or demand a substantially higher yield from a callable brokered CD.

For example, as I’m writing this, Fidelity shows the best 5-year brokered CD pays 5.2% when the yield on a 5-year Treasury is 3.89% but the best yield on a 5-year non-callable brokered CD is only 4.5%.

The yield advantage shrinks further when you adjust the Treasury yield for the state and local tax exemption. If we use the same federal marginal tax rate of 22% and state and local marginal tax rate of 6% in the example above, the tax-equivalent yield of the 3.89% Treasury is 4.21%. The 4.5% brokered CD only has a marginally higher yield than the Treasury. It’s more competitive in an IRA and in no-tax states.

Large Haircut When You Sell

If you want to get out of a brokered CD before it matures, you must sell it to a willing buyer. That’s the same for Treasuries but there are far fewer buyers for brokered CDs than for Treasuries. The buyer for your brokered CD will demand a substantial price concession to take over the CD from you.

Treasuries are highly liquid and competitive. If you must sell your Treasuries before maturity, you may get a lower price than your original purchase price but it’s going to be a fair price based on the market condition at that time.

Any slight yield advantage you have from a brokered CD over a comparable Treasury vanishes quickly if you must sell before maturity. Don’t even consider brokered CDs if there’s any chance you won’t hold them to maturity.

***

Before you explore whether it makes sense to buy a brokered CD, you should:

1. Decide what term you want because selling brokered CDs before maturity will be costly.

2. Check DepositAccounts.com for the best rate on a direct CD for your term. Weigh the convenience of brokered CDs against giving up yield and the early withdrawal option.

3. Check the yield on Treasuries for your term. Adjust it for the state and local tax exemption if you’re buying in a regular taxable account.

4. Only compare non-callable brokered CDs with direct CDs and Treasuries. Demand a large yield difference if you don’t mind callable CDs.

I give a detailed walkthrough of how to buy a CD at Fidelity or Vanguard in the next post: How to Buy CDs in a Fidelity or Vanguard Brokerage Account.

Learn the Nuts and Bolts

I put everything I use to manage my money in a book. My Financial Toolbox guides you to a clear course of action.

RobI says

Thanks Harry. I like seeing the convenience tradeoff in opening a new bank account vs making an existing broker purchase.

Can you clarify what payouts I get from a brokered CD ? Is it like a brokered treasury bond with a periodic interest payments at coupon rate plus the full original value of the CD at maturity?

Harry Sit says

It is like a bond. The payment frequency varies depending on the CD. If it pays quarterly, you get 1/4 of the annual interest paid out in cash every three months. See the “How a Brokered CD Works” section.

RobI says

Follow up question is how much I get back at maturity. Is is what I paid the broker or the full value when they were originally issued

Harry Sit says

The full face value, which is the same as the original amount paid for new-issue CDs. The purchase price on the secondary market can be higher or lower than the face value.

GeezerGeek says

Thanks! Very informative and in my case, very timely. I was looking around Schwab site and saw a CD from a bank offered at what looked like a decent rate. I bought it so that I could get a better return than the lousy bank rate Schwab that offers on loose cash. It was a three month CD and I had no idea what would happen when it came to term: cashed or reinvested. Now I know and have a much better understanding of what I bought.

GeezerGeek says

Just got a note from Schwab about my brokered CD: I will get my money from the CD two weeks after it matures. It seems odd and unreasonable that it would take two weeks to return the funds to me. That’s practically a half month’s interest lost.

Harry Sit says

That’s unusual. My previous brokered CDs all paid out on the maturity date. I’m curious whether this is specific to this CD, specific to Schwab, or just Schwab sandbagging by saying it could take up to two weeks but it actually doesn’t.

GeezerGeek says

Harry, you were about Schwab possibly sandbagging. The cash from liquidating the CD posted to my account the night of June 30, the day it matured. So the cash was in my account almost instantly after the bond matured without the two week delay that Schwab initially stated.

Harry Sit says

Thank you for the update. It’s great that it worked as expected.

Jim Sellers says

Thanks for this great article. I have a question about the tax equivalent yield. Why is the federal tax rate involved in the calculation? Why not just

t / ( 1 – s )?

Harry Sit says

Because you pay state and local taxes on the gross interest, and most people don’t get any extra deduction for the state and local taxes paid. They either take the standard deduction or have their state and local taxes already capped by the $10,000 annual limit. We want to make the yield equal after all taxes. It’s t * ( 1 – f ) for Treasuries and CD * ( 1 – f – s) for the CD.

Andrew says

Great article!

Very informative, thank you

Mark says

I live in Louisiana. I have a taxable brokerage account with Vanguard. I bought a brokered CD issued by a bank in California and I made $250 in interest. My question is, do I need to be concerned about potentially needing to pay California income taxes on that $250 interest?

Harry Sit says

No, it doesn’t go by where the bank is. As a Louisiana resident, you pay tax on the interest to Louisiana.

Mark says

Thanks for answering my previous question.

When comparing brokered CD’s that pay semi-annually and those that pay monthly, we have the opportunity for compounding by going with the monthly option and re-investing that interest each month. For example, a $240,000 CD paying 5% will pay $1,000 per month if it pays monthly. You could buy a new CD each month with that interest and effectively compound the interest. Therefore, the monthly paying CD is paying a higher effective rate of interest than the semi-annually paying CD, assuming the interest gets re-invested. (But even if you just spend the money you’re spending it before inflation can erode its buying power.)

I think I’ve made the case for the monthly CD, but if the semi-annual CD pays a higher interest rate, then maybe it’s better to go with the semi-annual CD instead. How much of a premium should I demand (in basis points) for settling for the semi-annual CD? I’m thinking 30 basis points is in the ballpark if we’re looking at the 5% range of interest. How to calculate this generally?

Harry Sit says

Using your example, investing $1,000/month at a 5% annualized rate gives you $6,062.85 at the end of six months (FV(5%/12,6,-1000) in Excel). A CD that pays $6,062.85 semi-annually on $240,000 will match that. $6,062.85 / $240,000 * 2 = 5.05%. Therefore you should demand a premium of only five basis points. You’re shortchanging yourself if you give up 30 basis points in favor of a monthly payout.

Lee says

The survivor option is a nice estate planning feature of a brokerage CD. I purchase discounted brokerage CDs in the secondary market for my 85+ year old relatives. When the time comes for the heirs to take over the accounts, they will have the option of receiving par value rather than market value if the securities need to be liquidated. This would increase the YTM over that stated at purchase since the discount would be realized early.

Mark says

Thanks again for your quick response. So, we’re looking at a 5 basis point advantage for the monthly versus the semi-annually, at least at the 5% range. Comparing monthly to annually paid, then we get a 10 basis point advantage, if I’m getting this straight in my head. If interest rates fall to 3% does the 5 basis point advantage still apply? I did some fiddling around with your formula using Open Office (needs semicolons for delimiters instead of commas, but seems to work the same) and it appears the 5 basis point advantage is the same for different interest rates.

Correct me if I’m wrong here, but there is also a 10 basis point penalty for buying the CD from another investor on the secondary market (at least with Vanguard) because there is a $1 commission per $1,000, as compared to no commission for buying it as a new issue. Vanguard charges the bank, as I understand it, so the investor gets the interest rate shown, it’s just the bank has to pay Vanguard as part of the cost of doing business.

This means if you are going to sell the CD on the secondary market you have to lower your price to offset that 10 basis point penalty the buyer is paying in commissions in order to be competitive with new issue offerings that pay the same interest rate. (But the buyer is also getting the accrued interest, I think. Not sure on this point as I haven’t ever bought one on the secondary market.)

Harry Sit says

If the interest rate is lower, the advantage of monthly payments will naturally be lower because you aren’t earning as much with the interest paid to you early. If the rate is 3%, monthly is worth two basis points over semi-annual and four basis points over annual.

If you try to sell the CD on the secondary market, you can only sell it to a dealer. The dealer will offer you a low-ball price. You’ll lose much more than 10 basis points. If you already own a brokered CD, pretend you want to sell and request a price bid. You’ll see how much you would lose if you sell.

Linda says

I am curious about the tax treatment of brokered (not original issue) CDs purchased at a discount. Assume that the purchase price of a $10,000 CD is $9,920, plus $0 accrued interest, plus a $10 broker’s fee. For this discussion, please ignore the tax treatment of the CD’s regular interest payments, which I understand. Upon maturity, would I report $80 of the $10,000 face value payment as interest and report a $10 capital loss, or will the $10 fee reduce the $80 interest amount or …?